This blog was written for the RSA Blog Student Summer Series that will highlight graduate student success in regional studies across the globe throughout the summer.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, select regions around the globe formed ‘travel/quarantine bubbles’ with imposed hard borders such as the ‘Trans-Tasman Bubble’ involving New Zealand and Australia and the ‘Baltic Bubble’ of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. These regional undertakings became safe havens in the global sea of COVID-19 cases, and offer a unique class of case study for our understanding of regions and regionalism. Though most bubbles occurred at the state-state level, this article will introduce a subnational bubble formed in eastern Canada (Image 1).

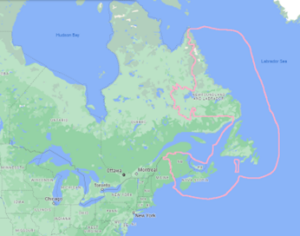

Image 1: The Atlantic Bubble with approximate terrestrial and maritime boundary

Forming a “covid-island”

In the aftermath of the initial wave of the pandemic to hit this region, a “covid-island” (a covid-archipelago) formed that was called the ‘Atlantic Bubble’ which endured for approximately 40% of the 2020 calendar year. The Atlantic Bubble encompassed the four most-easterly provinces within Canada: Newfoundland and Labrador (NL), Nova Scotia (NS), Prince Edward Island (PEI) and New Brunswick (NB), commonly referred to as Atlantic Canada. It was announced on June 24, 2020 via the Council of Atlantic Premiers and first appeared on July 3, 2020 and disappeared on November 23, 2020, after the Canadian island province of PEI (connected by the Confederation Bridge to NB, and by seasonal ferry to NS) and the coastal-island province of Newfoundland and Labrador (connected to NS by year-round ferry) suspended their participation, owing to the rising case numbers in NB and NS

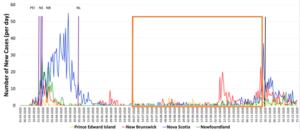

In Figure 1 below: the purple vertical lines are the establishment of internal border controls, the orange box the Atlantic Bubble period, and the black vertical line the terminus of the NB-NS border regime which had carried on.

Figure 1: Number of new COVID-19 cases per day in Atlantic Canada (March-December 2020)

Hardening and widening of internal borders

To understand the Atlantic Bubble, it is important to understand the borders both externally and internally which delineated it. Externally, the Atlantic Bubble (via NB) shared a terrestrial border with the USA state of Maine that was 513 kilometers, as well as an international maritime border. An international maritime boundary was also shared with France, through its overseas territory of St. Pierre and Miquelon (the small outlined keyhole in Image 1). Further, two separate portions of land border, covering approximately 4000 kilometers, and a maritime border involving a vehicle passenger ferry (to the Iles de Magdalene) connected with the Canadian province of Quebec (via NB, NL and PEI respectively).

The Atlantic Bubble involved a targeted and geographically limited easing of travel restrictions for residents of the hardened internal subnational borders within the region, initially established by their respective subnational governments, in concert with measures taken by the federal government to harden international borders to limit virus transmission and spread. Each of the four provinces constructed and manned border checkpoints which did not exist prior to the pandemic. It is this hardening and widening of internal subnational borders, as illustrated in the example of Prince Edward Island from Images 2 and 3 below, alongside the domestic travel restrictions which is of interest from a Canadian federalism lens.

Ordinary residents of the four provinces were afforded the opportunity to travel inter-region without any quarantine regime, while any approved visitors/travelers from outside (including other Canadians) were subject to a mandatory fourteen day quarantine period. It should be noted that the creation of the Atlantic Bubble flowed from the regional intergovernmental institution, the Council of Atlantic Premiers, which is unique in Canada for being the only such permanent, resourced and established body in the country.

Image 2: PEI COVID-19 Border Checkpoint in Borden, PEI (immediately off the Confederation Bridge linking PEI and New Brunswick) in May 2021. The same setup was in place during the Atlantic Bubble.

Image 3: PEI COVID-19 Border Checkpoint in Borden, PEI (immediately off the Confederation Bridge linking PEI and New Brunswick) in May 2022 (erected November 2021).

Impacts of the “Atlantic Bubble”

So, what does this all mean regionally? The RSA website informs that “regions are a key spatial scale for examining the nature and impact of political, economic, social and environmental change and innovation” and I believe that this holds quite true for Atlantic Canada. There is a divergence of opinions and viewpoints on held within the region with long histories and strong, distinct, and at times conflicting, identities held at the provincial and sub regional level (Newfoundland remained a British colony until 1949). Indeed, PEI, NB and NS are known as “the Maritimes” and one prominent historian just after the turn of this century stated, ““[Atlantic Canada] is not a region in any academic sense of the term. (…) [It] does not exist, except perhaps in the recesses of the Ottawa bureaucratic mind” (Ottawa being the capital city of Canada).”

For the 145 days of the Atlantic Bubble, Atlantic Canada became a place of envy and want owing to its exclusive status as a covid-archipelago haven. Suddenly, residents in other regions of the country were taking notice and wanting in, counter to the long-standing metropole narrative of Atlantic Canada as a peripheral region of limited opportunities and permanent habitation appeal. From a vantage point within the region, it was now being defined as what it did have: a seemingly safe idyll space where subnational, non-quarantine inter-provincial travel was permitted to residents; somewhere where the “new normal” was being put into practice. One wonders whether this experience has led to a softening of distinct sub-regional or provincial identities because of what the Atlantic Bubble (literally) encapsulated. The period of the Atlantic Bubble would seem to be a relative high point in the recent history of an externally created regional identity which (if Conrad is to be believed) began as a bureaucratic catchment area.

As a native (PE) Islander (by extension also a Maritimer and Atlantic Canadian), my scholarly interest has been piqued in seeking to uncover how the Atlantic Bubble as a policy construct was initially conceived, how it was operationalized and implemented into being. My doctoral research is delving into this matter to better understand of how this policy change came about and how the Atlantic Bubble covid-archipelago was conceived, designed and implemented. Islands come and islands go and are shaped by human, geological and earth science processes, across spatial and temporal aspects. Interestingly, while the geography which constituted the Atlantic Bubble remains, the covid-archipelago itself has vanished.

Andrew Halliday is a Ph.D. student in the Interdisciplinary Studies program at the University of New Brunswick (Saint John) located in New Brunswick, Canada. His professional and academic background is in public policy and public administration, comparative politics and island studies. He is a member of the Canadian Political Science Association and the International Small Islands Studies Association. His doctoral research examines the unique policy response to COVID-19 in the Atlantic Canadian region by means of the subnational Atlantic Bubble. He welcomes any feedback or inquiries based on this submission and can be reached at andrew.halliday@unb.ca.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.