The growing dominance of cities in our world appears to be inevitable as nowadays the majority of the world’s population lives in cities. Cities not only quantitatively outnumber but are also qualitatively outperforming all other places. This cosmopolitan urban future is, however, increasingly challenged by villagism.

Many big cities profited from neoliberal policies introduced in the late 20th century. Western states could not prevent the decline of their economic strength. This legitimised neoliberal policies supporting the most competitive and successful entrepreneurs. Whereas industrial production was spread by the welfare state over the national territory, now the new service and high-tech industries concentrate in urban areas. Cities and especially regional and global networks of cities provide the right kind of interactive milieu between related companies, research and educational institutes to stimulate innovation and become globally competitive.

“New middle class” and Competition

The growing importance of cities is rooted in neoliberal economic policies but is also part of a much broader societal transformation from industrial to late modernity. The industrial mass society has transformed, according to Andreas Reckwitz, into the society of singularities. Not only do products have to be outstanding in price and quality to compete on global markets. Excelling has become the norm which permeates all walks of life.

The social logic of competitiveness, based on being singular, is linked to the rise of the new middle classes in cities. They are well-suited to compete in the new economy based on their individual educational achievements. Cities provide the support base for many individuals to succeed. This contrast with declining opportunities many regions can provide to compete in globalising markets. There, large sections of the skilled workers degraded into a precariat doing temporary routine jobs. Competition in the society of singularities is based on the winner-takes-all principle. As a result, those who lose out in the competition not only lose out materially. They are marginalised and excluded as inferior and abject.

The self-image of the new middle classes is based on some singularly successful role models, whereas their devaluation of the precariat is based on its most offensive extremes. Educational failures, unhealthy behaviour, unstable families, public demonstrations of excessive consumption, and hedonism are in the polarising public debate interpreted as proof of their moral inferiority and the cause of their economic plight. The assumed clinging to a traditional way of life, gender roles, and a general aversion to social change by the precariat is opposed by the new middle classes and has become part of their cosmopolitan identity discourse.

In my book Political Geography of Cities and Regions: Changing Legitimacy and Identity, I argue that this rise of vertical villagism is part of the current shift in dominance from the relational perspective to the territorial perspective on legitimacy. These cover different aspects of legitimacy.

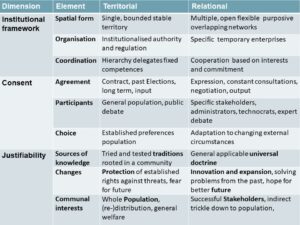

The ideas on what is a legitimate institutional framework, how to organise consent and how policies are justified differ widely. The main distinctions between both perspectives are outlined in figure 1.

The rise of vertical villagism and national populism challenges are no passing political phenomena but are part of a cycle of alternating dominance of what is legitimate governance. This is depicted in figure 2.

Opposition to narrow-minded policies like BREXIT must therefore go beyond rejections of specific policies, and can only succeed when these fundamental differences are better understood.

The revenge of the village and “Vertical Villagism”

Villagers themselves characterise their communities along similar lines but value these positively. Villagers frequently use conservatism and the importance of traditions to characterise their local identity. Differences in traditions and historically developed ways of life have are used in the traditional rivalry between villages. This local rivalry is also driven by the competition between neighbouring villages to attract business and state funding. This can be labelled horizontal villagism, focussing on the expressions of the distinctiveness of villages.

Vertical village identity concentrates instead on the similarities in underlying core values with other villages and is focused outward on the collective defence against unwanted urban influences. Vertical villagism focuses on their shared village-based community values, which sets them apart from the cosmopolitan urban society. Horizontal village identity discourses are based on specific elements within a village and differences between villages. Vertical villagism is based on general similarities between villages and their differences with cities. The protection of the villages has in vertical villagism a more outward focus. It focuses on cooperation with other villages to control external urbanising influences from either specific nearby cities or the cosmopolitan society of singularities in general. This results in the growing NIMBY like opposition to new projects in metropolitan regions and the rise in national populism.

This revenge of the village is part of the current crisis in legitimising neoliberal and cosmopolitan politics. These are rooted in fundamentally different and coherent visions on legitimacy. These differences are not new but have deep historical roots.

Kees Terlouw (Twitter, Website) is in the Department of Human Geography and Spatial Planning at Utrecht University.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.