Michael Dunford, Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

Weidong Liu, Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

Qing Ren, Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

ADP Editorial Team

ADP session at the International Geographical Congress (IGU)

Just as 1945 and the early 1980s were important turning points in global development so too is the present. These changes raise major challenges for scholarly research and for policy and politics. The objects of research and the research traditions of the recent past need to be interrogated and re-assessed. New foci of research and new perspectives are required to address contemporary problems and issues.

Amongst these changes is the end of the United States and NATO dominated unipolar world system established after the collapse of the Soviet Union and Communism in Eastern Europe. This change is a result of the relative decline of developed countries on the one hand and the rise of emerging powers on the other. And these two trends are associated with movements in the direction of a multi-polar world system which recognizes that this world is one of many civilizations.

These trends in global development derive in part from the wave of globalization that dates from the middle of the 1970s. Another cause was the generalization of neo-liberal economic ideologies. Yet another was the drive in a unipolar world to extend western values and western political systems to all parts of the globe with colour revolutions and in some cases war. These steps undermined the principles of sovereignty and balance of power that had underpinned the post-World War Two international order on the one hand and marginalised other voices on the other.

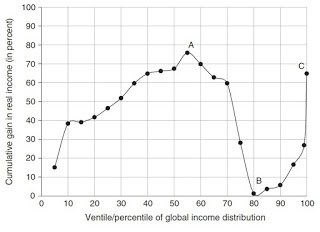

As Lakner and Milanovic’s ‘Elephant Chart’ suggests, the winners from this phase of development comprised two groups whose incomes grew strongly from 1988 to 2008. The first was the upper, middle and lower middle income citizens of emerging economies (China, India, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia). The second was the super-rich who mainly reside in what CitiGroup in 2005 called plutonomies (developed countries defined by massive wealth and income inequalities) and offshore tax havens. The apparent losers were the world’s poorest mainly in sub-Saharan Africa and countries devastated by war on the one hand (around the lowest percentiles) and the working and lower middle classes in rich countries (North America, Western Europe, Oceania, Japan) who were around the 80th percentile. The causes were of course not just economic globalization: domestic deregulation, tax cuts, automation, an inability to create sufficient new stable, well-paid jobs, new technologies, economic migrants and refugees all played a role.

The rise in income in some developing countries reflects the way in which first Japan, the four Asian Tigers, and other developing countries including in particular China, India and a number of other Asian economies successively managed to exploit the advantage of backwardness, finally spurring demand for mineral exports from Africa and elsewhere.

These countries that grew were all countries that did not pursue the neo-liberal agenda of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Washington Consensus countries in Latin America, Africa and some transition economies were increasingly subjected to capitalist market logic. Transnational capital was granted increasing global economic and political power, and decision making was increasingly permeated by multinational companies, transnational media organizations, investment banks, hedge funds, credit rating agencies, accountancy firms, management consultancies and international organizations controlled by western powers and promoting western values.

More recently, to the secular slowdown in western economic growth, and the economic crisis that had opened with the western financial crisis was added a political crisis reflecting deep social and political divisions in developed countries, a lack of secure and evenly distributed living standards and the deficiencies of the western political order and political establishment.

The stagnation of high income countries has depressed international trade, while investment also declined. The weakness of demand contributed to slower growth of many emerging economies. Chinese growth on which world growth increasingly depended has also slowed in a world in which low growth and high levels of inequality dominate political agendas.

A response in some quarters is a move in the direction of de-globalization. Globalization did not just involve increased economic interdependence which is moreover not easily unravelled. Globalization also involved increased ecological, political and social interdependence. Today many people and many things from diseases to dollars to news and greenhouse gases can reach almost anywhere in the world. As a result what happens in one place affects others, what one person does affects others requiring an operating system in which obligations to others are examined and negotiated.

At a time therefore when the neo-liberal globalist agenda is under attack, other countries such as China are attempting to map out a new model of inclusive globalization that is capable of serving the needs of everyone, that benefits all countries and people, addresses inequality and poverty and manages global risks. China has suggested a morality/justice-interest (Yi and Li – 义and 利) concept of international relations, and has proposed a Silk Road Economic Belt, a 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, an Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) and a national Silk Road Fund. India’s 2014 Project Mausam aims to re-establish maritime communications between countries of the Indian Ocean world, while a North-South International Transport Corridor from India via Iran, Azerbaijan, Russia and Europe is under development.

Aimed at Eurasian integration China’s Belt and Road Initiative is driving infrastructure (roads, railways, ports, airports, telecommunications networks, pipelines, development zones and cities) and economic development diversifying trade routes and reducing dependence on the Straits of Malacca. The US$ 46 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) connects relatively underdeveloped southern Xin Jiang and neighbouring landlocked countries in Central Asia along the Karakoram Highway through northern Gilgit-Baltistan to the megaport of Gwadar in the Arabian Sea on the Indian Ocean rimland. Other corridors will connect western China with Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, the Maldives and West Africa, while others will connect it westwards with the rest of Eurasia.

It was with these, amongst other, considerations in mind that, in 2015, the Regional Studies Association set up a new journal called Area Development and Policy, housed in the Institute of Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and published by Taylor & Francis. Prof. Michael Dunford and Prof. Weidong Liu are the Managing Editors. Ren Qing is the Editorial Assistant. A distinguished group of Editors from China, Russia, India, Africa, South Korea, Latin America and North America was established along with a distinguished international Editorial Advisory Board.

The journal was initially aimed at publishing research about and from the developing world in Eurasia and the global South. The intention was that the exchange of ideas would see the development of theories and interpretations reflecting the experiences of different countries in a world of many civilizations and contribute to mutual awareness and co-operation. The intention was also to reflect from these worlds on the relationships between them and the developed world. As change accelerates however the journal will pay more attention to the relations between all parts of the world.

The journal is entering its second year and has already published four issues, including research dealing with national, regional, urban, rural and local development trajectories of Brazil and Mexico in Latin America, Africa, India, Iran, Pakistan, China, Russia and East Asia. These articles have dealt with the geopolitics of Amazonia, industrialization, global value chains in the machine tools and IT sectors, urban-rural integration, land expropriation, infrastructure investment, and the politics of developmental states. Other articles have started to explore new macroeconomic geographies and the impact on global development of rising powers (see the Appendix).

The aim of this short article however is to invite you readers to rise to the challenge of analysing the different dimensions of these transformations that are reshaping the world in which we live and to read some of the articles already published. The papers so far published are listed in the Appendix which follows. Please also do submit your own research and contribute to debates about the transformation of our world.

Appendix

Volume 1, 2016 Issue 1

Area development and policy: an agenda for the 21st century

Michael Dunford, Yuko Aoyama, Clélio Campolina Diniz, Amitabh Kundu, Leonid Limonov, George Lin, Weidong Liu, Sam Ock Park & Ivan Turok

Geopolitics of the Amazon

Bertha K. Becker

Getting urbanization to work in Africa: the role of the urban land-infrastructure-finance nexus

Ivan Turok

Land acquisition in India: The political-economy of changing the law

Sanjoy Chakravorty

Regional cultural diversity in Russia: does it matter for regional economic performance?

Leonid Limonov & Marina Nesena

China’s evolving role in Apple’s global value chain

Seamus Grimes & Yutao Sun

Population growth, land allocation and conflict in Mali

Mark Skidmore, John Staatz, Nango Dembélé & Aissatou Ouédraogo

Urban–rural integration drives regional economic growth in Chongqing, Western China

Weidong Liu, Michael Dunford, Zhouying Song & Mingxing Chen

Volume 1, 2016 Issue 2

Brazil: accelerated metropolization and urban crisis

Clélio Campolina Diniz & Danilo Jorge Vieira

Repositioning Yunnan: security and China’s geoeconomic engagement with Myanmar

Xiaobo Su

South–south mobility: economic and health vulnerabilities of Bangladeshi and Nepalese migrants to India

Lopamudra Ray Saraswati, Avina Sarna, Ubaidur Rob, Mahesh Puri, Roopal Jyoti Singh, Vartika Sharma & Amitabh Kundu

The BRICS’ impacts on local economic development in the Global South: the cases of a tourism town and two mining provinces in Zambia

Peter Kragelund & Pádraig Carmody

Multifamily housing construction in Russia: supply elasticity and competition

Tatyana D. Polidi

Social inequality, city shrinkage and city growth in Khuzestan Province, Iran

Ahmad Pourahmad, Amir Reza Khavarian-Garmsir & Hossein Hataminejad

Volume 1, 2016 Issue 3

Rising powers and the drivers of uneven global development

Ray Hudson

Reorienting the drivers of development: alternative paradigms

Yuku Aoyama

Macroeconomic geographies

Jamie Peck

Inclusive globalization: unpacking China’s Belt and Road Initiative

Weidong Liu & Michael Dunford

The Silk Road goes north: Russia’s role within China’s Belt and Road Initiative

Mia M. Bennett

Reflections on China’s Belt and Road Initiative

Stanley Toops

Polycentric versus hierarchical tertiary centres: comparing San Diego and Tijuana

Tito A. Alegría

Innovation development of large companies in Siberia

Sophia Khalimova

Volume 2, 2017 Issue 1

Rethinking the East Asian developmental state in its historical context: finance, geopolitics and bureaucracy

Henry Wai-chung Yeung

The post-Soviet evolution of the Russian urban system

Evgeniya Kolomak

Land-use conflict and socio-economic impacts of infrastructure projects: the case of Diamer Bhasha Dam in Pakistan

Muazzam Sabir, André Torre & Habibullah Magsi

Districts and networks in the digital generation music scene in Mexico City

Alejandro Mercado-Celis

What matters for regional industrial dynamics in a transitional economy?

Canfei He, Shengjun Zhu & Xin Yang

Industrial upgrading and interaction between the advanced small south and China: the case of Taiwan’s machine tool industry

Liang-Chih Chen & Shiuh-Shen Chien