Authored by Simona Iammarino, Maryann Feldman, and Frederick Guy

Why, in advanced economies today, have we seen such regional polarization, between new wealth and the left behind? We answer this question by studying the interaction of three phenomena, which have too often been treated as distinct: one geographical, one of market structure, and one financial.

The geographical aspect is the importance of agglomeration economies to the productivity of firms, and to the wealth of places. Many of the places of prosperity have also become essential nodes in multinational production and innovation networks, enhancing virtuous cycles of economic growth. Second, it has become clear that the years since 1980 have seen a substantial rise in the market power in the U.S. due to a combination of new network technologies and the retrenchment of both regulation and anti-trust enforcement. This has occurred in many industries, but it is particularly striking in the case of global companies in ICT. Third, the financial sector has grown and has come to exert much greater influence over non-financial firms, a phenomenon sometimes called “financialisation”.

We argue that market power interacts with, and magnifies, agglomeration economies, turning the prosperous cities and regions into fortresses that prevent the entry of geographical as well as corporate rivals. Moreover, in a world with growing and spatially concentrated monopolies, the power of finance to extract free cash flow from less profitable firms implies stripping assets from the left behind places and investing them in the clusters of monopoly.

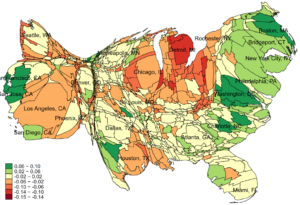

Let’s look at the geographic distribution of income. Figure 1 shows the change in the share of employed people with earnings above the 80th percentile, or the top 20% of the US earning distribution, between 1980 and 2016. In 1980, the highest concentration of well-paid workers was in Gary, Indiana – a steel manufacturing centre just east of Chicago – followed by Detroit, and Washington DC. The biggest gains in concentration of well-paid workers were in the San Francisco Bay area, Washington DC, Boston, and some secondary hubs in banking (Charlotte, North Carolina) and technology (Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill, North Carolina; Austin, Texas). Gains shown in places like Seattle, San Diego (both tech) and New York (finance) were more modest, but those places were starting from a very high base.[1]

Even more striking is the collapse of the good job share across the industrial heartland, including yesterday’s technological leaders like Detroit, and Rochester NY (home of Kodak and Xerox). In 1980, Detroit, together with the steel manufacturing city of Gary, Indiana, just east of Chicago, had been the only places ranking above Washington DC in share of well-paid jobs.

Some sunbelt metropolises, like Houston and Los Angeles, also lost ground – what we’re seeing here is not the triumph of the city, but the triumph of some cities. The notable concentrations of well-paid jobs are of three types: technology clusters, finance, and the federal government (the last being Washington, DC).

Figure 1. Top 20% of the US earning distribution, change 1980-2016, commuting zones scaled by population.

Technology clusters that should have a lot of well-paid jobs may hardly seem surprising: they require high skills; agglomeration (specifically, localization) economies bring lots of firms close together. The usual policy remedy to that is for a left-behind place to try to become a tech cluster in its own right, to find a tech niche and start building its own localization economies. The high pay in technology centres, however, is not all due to productivity rooted in a mix of skill and agglomeration economies: much of it is due to the market power of firms. That market power also makes it harder for other clusters to get a toe in the door; and, combined with the power of finance, it actually bleeds resources out of the left behind places.

When you see high wages in the San Francisco Bay area – the Silicon Valley – think Google, Facebook, Apple, Oracle, Cisco, Nvidia, Intel, Pixar, Uber, Airbnb, Hewlett Packard… the list goes on. Not only the technology, but the market power, is mighty. And that is just the richest, and most conspicuous, case of a wider phenomenon. Monopoly, or more generally, market power and cost-price markups, have grown in the U.S. (Eggertsson, Robbins, and Wold 2018). Digital technologies allow network economies – situations in which, as the number of users rises, the average value to the consumer rises, or the average cost falls (Kenney and Zysman, 2016).

Many economic activities benefit from network economies, and the problem of their regulation is as old as the division of labour. In the early twentieth century governments faced monopoly control of new networks in services such as electric power distribution and telecommunications. While today’s digital networks present some of the same issues, the geography of regulation has changed. When the network is a grid for the distribution of electric power, the geographical scope of the monopoly is approximately co-extensive with the monopoly’s physical assets and places of employment, and may be regulated (or owned) by a state or local government: for much of the twentieth century, a distinction was made between local and long distance telephone services, which were regulated differently. Today’s digital platforms typically project market power over a much wider – often global – territory, and to their home bases represent valuable export industries for which government has limited motivation to regulate. In addition, digital platform monopolies make their money by controlling our access to previously open networks. Relationships with consumers are mediated and controlled by platforms, and knowledge about consumer preferences is a knowledge asymmetry difficult for new entrants to overcome (Zuboff 2019).

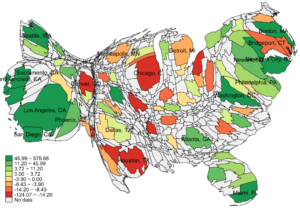

A rough indicator of monopoly power is given by the ratio of market valuation to book value – an approximation to Tobin’s Q. For each commuting zone for which we have this information for at least five non-financial firms in both 1980 and 2016, we calculate this ratio on an aggregate basis summing market valuation and assets across all firms in the area, and consider then the change in that ratio between the two years. Results are show in Figure 2, pointing to large rises in the ratio of the technology-heavy cites of the west coast and northeast, and declines in much of the industrial Midwest.

Figure 2. Ratio of company market value to book value of assets, change 1980-2016, commuting zones scaled by population (CZs with at least 5 non-financial firms in Compustat)

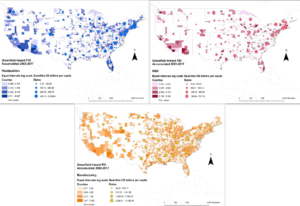

Monopoly can both amplify agglomeration economies, and create new external economies. The amplification can be seen in the enhanced value to companies of intangibles assets such as skilled labour and knowledge spillovers. Yet Silicon Valley was created as much by venture capitalists and intellectual property lawyers in the search for new business models as by the free flow of engineering knowledge (Kenney and Florida 2000; Suchman 2000). Many of the web- and IP-based platform monopolies shows a strong spatial concentration of headquarters in particular cities, the same locations that through FDI attract also multinational strategic functions such as regional headquarters and R&D relative to other, more dispersed, functions, such as manufacturing production (Figure 3).

Figure 3. FDI cumulative inflows 2003-2017, by county and state and function (only HQ, R&D and Manufacturing)

Far from offering a model that the left-behind places can emulate, big agglomerations of techno-monopoly actively hold other places back in three ways: by appropriating revenues which are effectively a tax on almost all business activities in most parts of the world; by restricting use of basic knowledge and thus degrading capabilities; and, in partnership with the financial sector, by diverting capital from other firms and regions. In spatial terms, this redistributes wealth from around the world, to the shareholders and employees of the platform companies – disproportionately found in a few privileged places. We will comment here briefly on the role of finance; for discussion of the “monopoly tax” and also the geographical restriction of knowledge and capabilities, see our working paper.

Monopoly has grown hand in hand with finance. Liberalisation of financial markets has given finance more power over non-financial firms, which help them drain capital from sectors where there is less market power, and invest where there are prospects for monopoly profits. This has led directly to the rapid growth of pay in finance (Philippon and Reshef 2012); thus, the presence of New York and Charlotte among those that gained shares of good jobs.

High financial dependency, or financialisation, has been described as one in which finance is disconnected from the real economy (various papers in Martin and Pollard 2017), and alternatively one in which finance rules the real economy (Lazonick 2010; Appelbaum and Batt 2014). What that means, in a world of spatially concentrated monopolies, is that capital flows into monopoly firms and the places in which they invest, and out of other firms and the places in which they are located.

The reduction of financial resources for left behind places has been intensified by the growing industrial and spatial concentration of commercial banking: between 1994 and 2018, the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) for spatial concentration (by commuting zone) of U.S. commercial banking grew from 0.0199 to 0.030 for deposits and 0.0497 to 0.1150 for assets (authors’ calculation from FDIC data). Bank headquarters are still more spatially concentrated, corporate finance more yet again; and the post-recession bank closures occurred disproportionately in small and medium sized cities and rural areas.

Some of the money drained from left-behind places makes its way to new companies via venture capital. Venture capitalists and their investments agglomerate in a handful of tech clusters and the city-regions that host them. In the U.S. this has reinforced relationships of spatial dominance and dependence – or territorial hierarchies – between monopoly-based clusters and areas relying on competitive industries (Audretsch and Feldman 1996; Susman and Schutz 1983).

Place-based policies have been long advocated; however, the revolt of places “that don’t matter” (Rodríguez-Pose 2018) requires new solutions. Local economic development policies that focus on generating increasing returns to place, finding the right industrial niche or smart specialization and attracting established companies or enabling entrepreneurs, have not generated sufficient results for the majority of the population. Efforts of US State Attorneys Generals and of the European Commission signal a realization that these platform business models are not a technological inevitability, but are due to governments’ failure to regulate the new networks adequately. Current strategies will never work if today’s regional income disparities are not only the product of agglomeration economies but the outcome of the exercise of monopoly power. While monopoly rents are shared with local employees, contractors and suppliers, producing concentrations of high wages within clusters of monopoly firms, monopolies are able to pull resources from other firms and regions to their location, reinforcing their advantage. This deprives other businesses, and their locations, of capital, revenue, and opportunity – in short, of the chance to generate income and prosperity. Incumbent giants and the search for new monopoly business models will continue to reinforce localised external increasing returns to create mega cities. Against these giants or, as they are increasingly called, star cities, it is difficult for other localities to claim any advantage.

[1] See the before and after maps (1980 and 2016) in our working paper: https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/29484/

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development, and want to elaborate your ideas in a different medium? The Regional Studies Association is now accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at RSABlog@regionalstudies.org.

References

Appelbaum, E. and R. Batt. 2014. Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Eggertsson, G.B., J.A. Robbins, and E. Getz Wold. 2018. “Kaldor and Piketty’s Facts: The Rise of Monopoly Power in the United States.” Working Paper 24287. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w24287.

Audretsch, DavidB, and MaryannP Feldman. 1996. “Innovative Clusters and the Industry Life Cycle.” Review of Industrial Organization 11 (2): 253–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00157670.

Kenney, M. and R. Florida. 2000. “Venture Capital in Silicon Valley: Fueling New Firm Formation.” In Understanding the Silicon Valley: The Anatomy of an Entrepreneurial Region, 98–123.

Kenney, Martin, and John Zysman. 2016. “The Rise of the Platform Economy.” In Issues in Science and Technology, 61–69. National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, Institute of Medicine, the University of Texas at Dallas, and Arizona State University.

Lazonick, W. 2010. “Innovative Business Models and Varieties of Capitalism: Financialization of the US Corporation.” Business History Review 84 (4): 675–702.

Martin, R., and J Pollard, eds. 2017. Handbook on the Geographies of Money and Finance. Cheltenham, UK, Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar.

Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2018. “The Revenge of the Places That Don’t Matter (and What to Do about It).” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (1): 189–209.

Suchman, Mark. 2000. “Dealmakers and Counselors: Law Firms as Intermediaries in the Development of Silicon Valley.” In Understanding the Silicon Valley: The Anatomy of an Entrepreneurial Region, edited by Martin Kenney, 71–97.

Susman, Paul, and Esther Schutz. 1983. “Monopoly and Competitive Firm Relations and Regional Development in Global Capitalism.” Economic Geography, 59(2): 161-177.

Zuboff, S. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. London: Profile Books.