Why are some places better governed than other? What explains corruption and low levels of public services overwhelming good governance practices? Many studies explain these differences by looking at cultural factors as determinants of corruption, including trust in society and trust in institutions. However, the correlation between well-being and good governance should not be simply explained by culture. If culture is the sole predictor, then the possibility of change is limited, since change in culture requires a long-term historical process.

Puzzled by this, the article Quality of Government and Regional Competition: A spatial analysis of subnational regions in the European Union (Bubbico et al. 2017) explores a short term factor that affects the level of Quality of Government (QoG), namely the level of spatial interdependence in QoG among subnational regions within the EU. The hypothesis is that the threat of businesses moving to nearby regions that are more suitable for business development leads to interregional competition. Furthermore good quality government can create advantages in the international competition for foreign direct investment. Combined, these reduce the chances of re-election of incumbent governments when government quality is low. This competition is shown to be a driving force behind the development of impartial institutions which is a core component of QoG.

Our model assumes regional governments act in order to increase the probability of re-election and that regional decision makers are able to affect the local level of QoG – at least when the region has a sufficient level of autonomy from the center. The direct benefit of an improvement in QoG is then the acknowledgement by voters through increased support for the incumbent government. High levels of QoG are shown to produce many positive side-effects, such as high levels of human development (Acemoglu et al., 2000; Rothstein, 2013; Charron et al., 2014). This voter reasoning is well established in the retrospective economic voting literature (Lewis-Beck & Stegmaier, 2013) and the established finding that corruption – one of the main components of QoG – is a predictor of vote choice (Ferraz & Finan 2011).

QoG requires impartiality when recruiting administration and implementation of policies, which requires dealing with corruption, as well as investing in government agencies and developing new policies and laws. Governments therefore will be reluctant to invest in such improvements unless there are clear incentives. In this sense, we build on the work by Ward & John (2013), who focus primarily on the extent to which policy makers learn from neighbors. Using a measure of competitive pressure, we demonstrate the level of QoG of a subnational region affects the level of good governance of its neighbors.

The empirical analysis supports our hypothesis that implementation of policies that encourage impartiality in governments, improvement of the quality of public services and reduction of the level of corruption, have an effect to similar policies in competitor regions. Regions that have similar levels of innovation and efficiency, where investors could divest their investments without additional cost, compete with each other by improving QoG – making QoG one of the main factors that attract investment. The regions improve their level of good governance when a competing region does so, in order to avoid losing investments.

In northern Europe the competition is at a wide regional level, with competitor regions competing across all northern Europe. The north European subnational regions have high levels of competition within and outside the borders of the country they belong to. Therefore, a drop of QoG in just one region affects neighbors negatively, who also reduce their good governance practices.

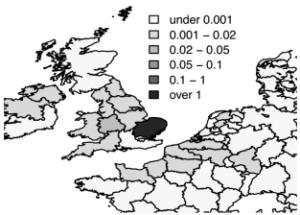

We offer two examples to describe this in context of north and south of Europe, precisely in two NUTS2 regions in England and in Bulgaria. QoG in British subnational regions is not strongly interdependent. Regions in Britain develop relatively independently, but respond to competitive pressure that affects regions outside of Britain in France, Netherlands, and Ireland. This interconnection is reciprocal. Increasing QoG by one standard deviation in ‘East England’ has a relatively modest immediate impact on a wide range of neighbors within and outside Britain. (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Increasing QoG by one standard deviation in ‘East England’ has a relatively modest immediate impact on a wide range of neighbors.

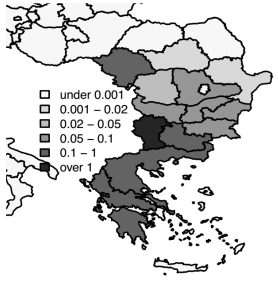

On the contrary, the competition among subnational governments in southern Europe demonstrates higher level of local interdependence (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Increasing QoG by one standard deviation in ‘Yugozapaden’ has a strong immediate impact on a few neighbors.

Meaning the regional impact of changes in QoG in south Europe will be magnified across neighboring regions. Therefore, if regions work together the QoG would be considerably higher just by competitive pressure. These effects will further expand to other competitive regions across south Europe. The high levels of interdependence in good governance in south Europe suggests that there are possible virtuous cycles, but also vicious ones. European Union policies to stimulate good governance practice in subnational regions should consider the potentially exacerbated effects, particularly in the south.

Antonio Bubbico is an Environmental Economist Consultant at the Agricultural Development Economics Division of the FAO. He has been a Research Fellow at University of Padua and a Postdoctoral research fellow at the University College Dublin. He got a Ph.D. (graduated in July 2014) in Agrifood Economics and Statistics at the University of Bologna with the title of Doctor Europaeus. He got a Master in Local Economic Development at London School of Economics. His research interests focus on environmental economics, climate change adaptation and mitigation, economic modelling, social capital, local economic development, GIS, spatial econometrics, big data and machine learning.

Johan (Jos) Elkink is Associate Professor in Research Methods for the Social Sciences at the School of Politics and International Relations of University College Dublin, teaching modules on statistics and research methodology. His research focuses on the application and development of statistical methods to the study of political science. His methodological work concentrates on the estimation of spatial econometric and network models with discrete dependent variables. He further works on the study of political elites in Russia, with a focus on understanding institutionalisation, personalisation, and patronage networks; and voting behaviour, focusing on the impact of political knowledge and uncertainty on voting decisions.

Martin Okolikj is a post-doctoral researcher at KU Leuven, Centre for Citizenship and Democracy, working on the 2019 Belgian Election Study. His primary research interests are in the fields of Political Methodology and Comparative Politics, with a particular focus on Elections, Voting behavior and Quality of Government. His research appears in several international peer-reviewed journals, such as ‘European Journal of Political Research’, ‘Politics and Governance’, and ‘Irish Political Studies’. Martin holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from University College Dublin.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development, and want to elaborate your ideas in a different medium? The Regional Studies Association is now accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at RSABlog@regionalstudies.org.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S. & Robinson, J.A. (2000). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. Cambridge,MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bubbico, A., Elkink, J.A. & Okolikj, M. (2017). Quality of government and regional competition: A spatial analysis of subnational regions in the European Union. European Journal of Political Research 56(4): 887–911.

Charron,N.,Dijkstra, L.& Lapuente,V. (2014).Regional governance matters: Quality of government within European Union member states. Regional Studies 48(1): 68–90.

Ferraz, C. & Finan, F. (2011). Electoral accountability and corruption: Evidence from the audits of local governments. American Economic Review 101(4): 1274–1311.

Lewis-Beck, Michael S. and Mary Stegmaier. 2013. “The VP-function Revisited: A survey of the literature on vote and popularity functions after over 40 years.” Public Choice 157(3–4):367–385

Rothstein, B. (2013). Corruption and social trust:Why the fish rots from the head down. Social Research 80(4): 1009–1032.

Ward, H. & John, P. (2013). Competitive learning in yardstick competition: Testing models of policy diffusion with performance data. Political Science Research and Methods 1(1): 3–25.