Chandrima Mukhopadhyay received her PhD from School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK in October 2014. She was the recipient of a competitive PhD Studentship on Spatial Planning and Environment. She has taught at CEPT University, India and was recently a visiting scholar at MIT-UTM Malaysia Sustainable Cities Program. She has published in Town Planning Review, Journal of Infrastructure Development, Progress in Planning, Landscape Research and Planning Theory and Practice. She is also the editor at PlaNext, and Conversations in Planning.

Regional futures is an important topic to be discussed in the context of the global South since cities and regions will be largely urbanised in the coming decades. There are multiple dimensions to consider: the larger scale of urban settlements in the context of the global South; economic competitiveness; planned or unplanned urbanization (since planning is no longer merely a public sector activity); as well as the optimal use of resources and low carbon development for addressing climate change. This research is a follow-up to the policy brief (here) and a blog on megaregions in the context of global south (here), which focused on Asia. While the idea of a ‘mega-region’ as relevant to global south is in a comparatively premature stage, ‘mega urbanization’ is already widely used, both in South Asian and East Asian contexts (Datta and Shaban, 2016; Webster, 2014). Architects, urban designers, and physical planners have shown keen interest in the larger scale of urban form/urban settlement, as related to planetary urbanization. The concept has been studied through an interdisciplinary approach, also argued to be the right approach towards ‘regional science’ or ‘regional studies; ’ however, as discussed below, there remains scope for improvement.

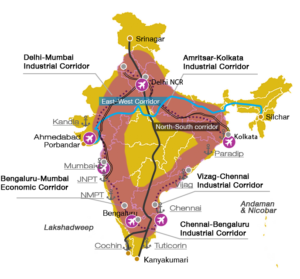

Conceptually, mega-regions are suggested to be economically more competitive than smaller urban settlements. While the debates on mega-regions in the global North have discussed ‘emerging mega-regions’, the discussion in the context of China has been about implementing ‘mega-regions’ as a strategy including a low carbon development dimension (Yang et al., 2014). The case for five proposed economic and industrial corridors in India are examples of such ‘strategically’ planned mega-regions. In addition, these corridors are about ‘rural to urban transformation’, ‘planned urbanisation’, ‘industrialisation’ (improving the return from land), and to some extent, includes the question of ‘planetary urbanisation’.

It is argued that regional study/science is interdisciplinary, although, especially in the light of climate change, the use of knowledge from multiple disciplines is not obviously evident in proposals for planned urbanization. It is argued elsewhere that land use change has implications for climate policy, to be specific, for GHG emission. There are numerous other parallel interdisciplinary studies, where scholars are working on climate change, adaptation, land use change etc. There is little interaction between these interest groups so far. It is important that planners working on these corridor projects draw from and effectively use knowledge from such interdisciplinary studies. One main barrier to such interaction could be strong economic development interest of the central government, and the influence of industrialists.

The following table provides some basic data about proposed five economic and industrial corridors.

Table 1. Basic data about proposed economic and industrial corridors in India.

| Corridor | Length of freight corridor/ Geographical area | Forecasted population | Forecasted investment | Foreign Investment |

| Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor

|

1500 km. | (Expected to generate 3 billion job) | USD 139.1 Billion | Equal share by India and Japan |

| Chennai Bengaluru Industrial Corridor

|

49,230 acre (three nodes) | 2.85 million (both residential and day-time) | USD 10,829 million | |

| Mumbai Bengaluru Economic Corridor

|

1000 km. 143,000 km2 | 2.5 million job creation | USD 42 Billion. | |

| Amritsar Kolkata Industrial Corridor

|

1839 km. (150-200 km on both sides.) | USD 800 million (first phase) | ||

| Vishakhapattanam Chennai Industrial Corridor

|

800 km. | USD 2.8 billion (Over five years) |

Currently the focus is on promoting investment opportunities to the industry in these corridors; with substantial foreign investment in the mega-projects. Vishakhapatnam Chennai Industrial Corridor, as part the of East Coast Economic Corridor strengthens India’s strategic relation with South East Asia and ASEAN countries.

Figure 1. India’s five proposed economic and industrial corridors (The pink band showing the extent of corridor development) Source: https://www.exportjet.com/invest-in-india/

Table 2. Economic indicators for the states covered by proposed economic and industrial corridors (2011 Census data).

| Corridor | States | Main workers involved in agriculture related job (%age) | Main workers (%age) | Marginal workers (%age) |

| India-wise figure | 52.45 | 30.43 | 11.09 | |

| Delhi Mumbai Industrial corridor | Delhi (NCT) | 1.38 | 31.6 | 2.37 |

| Uttarpradesh | 58.09 | 22.33 | 15.3 | |

| Haryana | 42.99 | 27.67 | 10.73 | |

| Rajasthan | 59.4 | 30.71 | 18.22 | |

| Gujarat | 48.72 | 33.69 | 9.05 | |

| Maharashtra | 52.12 | 38.94 | 6.93 | |

| Madhya Pradesh | 31.26 | 31.26 | 18.34 | |

| Mumbai Bengaluru Economic Corridor | Maharashtra | 52.12 | 38.94 | 6.93 |

| Karnataka | 51.9 | 38.29 | 9.13 | |

| Bengaluru Chennai Industrial Corridor | Karnataka | 51.9 | 38.29 | 9.13 |

| Tamilnadu | 42.47 | 38.72 | 9.10 | |

| Chennai-Vishakhapattanam

Industrial Corridor |

Tamilnadu | 42.47 | 38.72 | 9.10 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 59.5 | 39.06 | 10.98 | |

| Amritsar Kolkata Industrial Corridor | West Bengal | 41.68 | 28.14 | 16.6 |

| Jharkhand | 48.44 | 20.66 | 29.54 | |

| Bihar | 70.5 | 20.51 | 10.49 | |

| Uttarakhand | 46.4 | 28.46 | 14.3 | |

| Uttarpradesh | 58.09 | 22.33 | 15.3 | |

| Haryana | 42.99 | 27.67 | 10.73 | |

| Odisha | 55.1 | 25.51 | 25.16 | |

| Punjab | 37.89 | 30.46 | 7.64 |

Note: The first column shows percentage of main worker involved in agriculture related job (Cultivators, Agricultural labourers, Plantation, livestock, Forestry, Fishing, Hunting and allied activities).

Table 2 above shows the multiple states covered by each of the corridor, with economic indicators (using data from 2001 census as complete data for 2011 is not yet available). There is a varied share of corridors for each the states, with numbers showing uneven development indicators across multiple states. This indicates potential difficulties for delivering completed projects on time, whilst also maintaining the homogeneity of a region.

To conclude, the regional future of India lies in these mega-regions that will change the landscape of urban India in the coming years. These tools of strategic planning are supposed to use resources optimally and still achieve a higher rate of urbanization. The important aspects for future examination are: state-led versus market-led development; ‘fragmented’ development delivered by the private sector at urban extensions; unplanned urbanization sometimes created by displacement; and a regional approach towards development to ensure equal access to basic services for all citizens. With climate change having real impact on our livelihood, regional planning will have to embrace adaptive planning,[1] utilizing inter-disciplinary knowledge to solve this.

[1] From twitter: Simin Davoudi at RSA conference.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development, and want to elaborate your ideas in a different medium? The Regional Studies Association is now accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at RSABlog@regionalstudies.org.