Economic cohesion and convergence lie at the heart of the European project. Recently, these objectives have been undermined by the 2008-2009 financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic. Now, they are at risk again as Europe seeks to green and digitalize its economy.

The findings of our study Technological Capabilities and the Twin Transition in Europe however underscore that Europe’s regions – developed, transition, and less-developed – can all contribute to and benefit from this twin transition. Together, European regions have the research and innovation capabilities to do so.

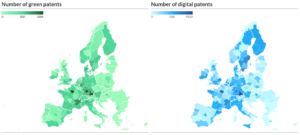

High concentration of technological capabilities

Today, more developed EU regions produce most of the technologies that digitize and green the economy. More than 80% of these technologies are developed in areas already well ahead in terms of growth, competitiveness, and prosperity.

Figure 1

Regions such as Upper Bavaria or the Île-de-France could gain even more as their greatest potential is in high-complex green and digital technologies, such as AI, Big Data, and cybersecurity. These complex technologies bestow huge competitive advantage and yield high economic returns.

In sharp contrast, we discovered that transition and less-developed regions, many in southern or eastern Europe, command relatively small shares of twin transition patents. Their greatest potential is in often low-complex green technologies: such as biocides, waste management, or greenhouse gas capture. They don’t have the bundle of capabilities required to develop twin transition technologies on their own. They lack an adequately skilled workforce, a strong institutional infrastructure, and good governance. Thus, these regions are at risk of being left behind again.

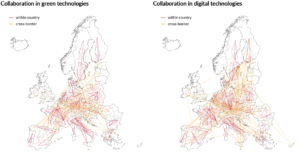

Collaboration pays off

But, critically, no one region – even the most developed one – have all of capabilities needed to develop all technologies for the twin transition. But regions can collaborate and thereby add up complementary capabilities. Our results are – again – at first sight disappointing: Europe’s regions collaborate on a relatively small scale, mostly within national boundaries. If they collaborate cross-border, more developed regions take the lead.

Figure 2

Much of the research infrastructure in Europe remains organised on a national scale. This reflects little coordination of research and innovation policies among EU member states.

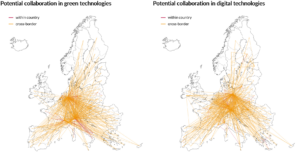

We also estimated the potential for collaborations between European regions to develop technologies for the twin transition. The untapped potential is huge, mainly cross-border, and spreads out over all European regions.

Figure 3 – Potential Collaborations

The study identifies collaboration opportunities for every EU region. Transition and less developed regions also exhibit lots of untapped potential. Indeed, we discover “hidden twin transition champions” within this groups of regions. Especially these regions have lots of technological capabilities they can share with others. If they reached out more to others – particularly to other less-developed and transition regions – they could spearhead innovative solutions to twin transition problems. Europe as a whole would benefit through greater cohesion technological progress.

What’s to be done?

Fostering inter-regional collaboration is a route for Europe to rediscover the path to greater economic cohesion. Especially lower-income regions must exploit their opportunities developing technologies fully to avoid a widening gap in economic prosperity in the twin transition. Therefore, policymakers need to remove bottlenecks hampering the exploitation of these opportunities. Improving the regional educational and research infrastructure and increasing the quality of regional institutional governance are two levers to start with.

Removing bottlenecks is a job for EU policymakers but not for them alone. Brussels should prioritise stronger inter-regional collaboration and, for instance, make it attractive for multi-national enterprises to invest in Europe. National governments and regional authorities should provide greater support for entrepreneurship, implement educational reforms and improving local governance. Specifically, policies must promote better, more extensive links between university and industry, including start-ups and clusters.

Above all, the EU must show that it means what it says. “The European Green Deal is on the one hand about cutting emissions, but on the other hand about creating jobs and boosting innovation,” Ursula von der Leyen said on assuming office as European Commission President. That must apply to all EU citizens – and all of Europe’s regions.

(pictured from left to right)

Julia Bachtrögler-Unger, an economist at the Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), specializes in regional economics and cohesion policy. She is also a member of the Austrian productivity board.

Pierre-Alexandre Balland is a professor at Utrecht University, visiting professor at the Center for Collective Learning of the Artificial and Natural Intelligence Toulouse Institute and research fellow at the Center for Complex Systems Studies. His research focusses on complex systems, the future of cities, artificial intelligence, and blockchain technologies. Additionally, he is a high-level policy expert currently advising the European Commission on innovation policy as part of the ESIR group.

Ron Boschma, a professor at Utrecht University and Stavanger University, specializes in evolutionary economic geography, the spatial evolution of industries, regional systems of innovation, the structure and evolution of networks, agglomeration externalities, and regional growth. He also provides policy expertise to various policymakers in Europe.

Thomas Schwab, an economist at the Bertelsmann Stiftung, focuses on European economic policy, with a particular emphasis on regional economic development and cohesion policy.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.