The following piece is a brief extract from a more comprehensive study on the impact of two trends in the context of Cohesion Policy: hyper-Lisbonisation and re-nationalisation. The article investigates how these trends are intertwined with the reiterative resort to employing Cohesion Policies funds outside of their original objectives and legal provisions, particularly to counterbalance the effects of recent global crises. This is actually threatening one of the main funding sources supporting EU growth and development within a social justice and territorial equity framework. The full version of the paper is available here (https://www.gssi.it/images/discussion%20papers%20rseg/2024/DPRSEG_2024-10.pdf)

EU Cohesion Policy is the world’s largest regional development program. Its main mission is to tackle Europe’s territorial disparities using long-term investments. The European Union has faced a series of profound shocks in the past fifteen years, including the 2008 financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the war in Ukraine. To mitigate the asymmetric socio-economic impacts of these crises, policymakers have increasingly diverted Cohesion Policy resources toward short-term recovery measures. This shift has reinforced two transformative trends.

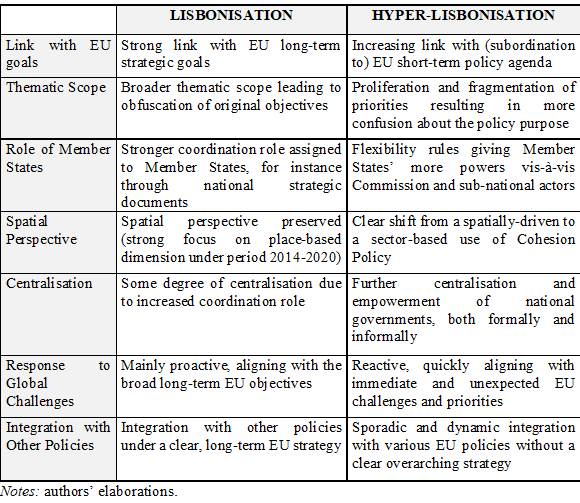

First, it has further strengthened the so-called “Lisbonisation” of the policy (Mendez, 2011), that is, its alignment with the EU’s overarching priorities, at the risk of diminishing its territorial development goals (the term “Lisbonisation” comes from the Lisbon Agenda, Europe’s strategic policy framework for the period 2000-2010). The increasing use of Cohesion Policy for crisis-mitigation purposes and emerging priorities has resulted in a state which we term “hyper-Lisbonisation” – not only is Cohesion Policy all the more directed to support the main long-term objectives of the EU (and their periodic revision), but, increasingly, its short-term political agenda. This is evident in the policy’s expanding thematic scope, which now includes a series of diverse and fragmented objectives, often at the expense of its original goals of territorial equity. For instance, during the COVID-19 crisis, Cohesion Policy funds were heavily redirected to health infrastructure in Southern and Eastern Europe, highlighting the shift from long-term spatial planning to reactive crisis management.

Second, a more pronounced alignment with EU priorities is giving impetus to a fresh “re-nationalisation” of the policy (Pollack, 1995; Bache, 1998) because, particularly in times of hardship, it inevitably entails a stronger coordination role for Member States relative to the spatial concentration and programming of the funds. For example, recent regulatory flexibilities permit significant fund transfers between regional categories, diluting the redistributive logic of the Cohesion Policy. While these measures improve responsiveness, they undermine place-based approaches and risk amplifying regional inequalities. This is particularly concerning for less-developed regions, which are often less able to advocate for their needs within national and European frameworks.

Amid the attempt to strike a difficult balance between competitiveness and cohesion, the two trends are shifting the Cohesion Policy’s objectives away from their primary focus on promoting territorial equity and reducing regional disparities. The fundamental principles of the policy – subsidiarity and place sensitivity – are being eroded in favour of a more space-neutral (or spatially blinded) and top-down logic.

The future negotiations for the EU’s post-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework will probably revolve not only around the overall budget but also the type of funding instruments (e.g., adopting or not a purely performance-based model akin to the one of the Next Generation EU program). Looking at the Letta and Draghi reports, it becomes of paramount importance to provide sound evidence on how territorial development could be best achieved in the face of future megatrends and how to reconcile this objective with the EU’s broader strategic priorities (e.g., defence, strategic autonomy) (see Bachtler et al., 2024).

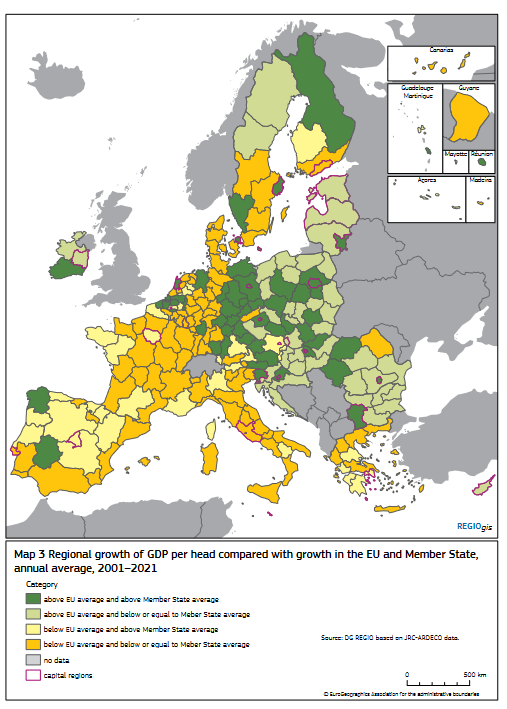

To this end, future research could contribute to critically evaluating the extent to which the Cohesion Policy’s shift towards re-nationalisation and (hyper)Lisbonisation may be generating new territorial imbalances. Three potential avenues are

- In-depth comparative case studies of several Member States to understand how the hyper-Lisbonisation and re-nationalisation trends manifest at different scales and in various governance contexts;

- An analytical focus on the allocation and impact of digital and green transition resources granted under the Cohesion Policy to assess whether the investments made are indeed promoting regional convergence or inadvertently contributing to the widening of disparities by favouring more developed regions—a concern central to the discussion of re-nationalisation.

- A critical investigation of Next Generation EU’s beneficiaries to examine whether and to what extent a stronger national coordination role still enables a spatial logic to reduce regional disparities, or if, in contrast, there is an emerging trend where the ‘winners’ – typically the most developed regions – continue to gain disproportionately.

In conclusion, if current trends persist, the Cohesion Policy risks becoming a flexible instrument for crisis management at the expense of its long-term objectives. Future policy reforms must prioritise place-based strategies and robust multi-level governance mechanisms to restore their original mission of fostering territorial equity and reducing disparities.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are purely those of the author(s) and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the Tuscany Region

Author

Francesco Molica is the Director of EURADA, the European Association of Development Agencies, and a doctoral researcher in Economics and Management at the Université libre de Bruxelles. He previously worked as an Economic and Policy Analyst at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, where he conducted research on regional and innovation policies. He also served as the EU Budget and Regional Policy director at the Conference of Peripheral Maritime Regions, the largest organisation and think tank representing EU regional governments. He has also authored several academic and policy papers on regional science, regional policy, and innovation policy.

![]() : Francesco Molica

: Francesco Molica ![]() : 0009-0005-9220-782X

: 0009-0005-9220-782X ![]() : fmolica

: fmolica ![]() : fmolica.bsky.social

: fmolica.bsky.social

Alessandra de Renzis is a member of the Cabinet Office of the President of the Tuscany Region and has long-term experience in programming and implementing local development strategies. She is also a Regional Science and Economic Geography doctoral researcher at Gran Sasso Science Institute in L’Aquila (Italy). Her works focus on territorial cohesion and inclusive growth by investigating the local determinants of development, particularly in peripheral areas.

![]() : Alessandra-de-renzis

: Alessandra-de-renzis ![]() : 0000-0001-9973-5696

: 0000-0001-9973-5696 ![]() : AlinaMure

: AlinaMure ![]() : alederenzis.bsky.social

: alederenzis.bsky.social

Sébastien Bourdin is an Economic Geography & Environmental Management Professor at EM Normandie Business School. He is also the Chairholder of the European Chair of Excellence on Circular Economy and Territories. With a PhD in Geography and an Accreditation to Supervise Research, his expertise lies in Regional Development, Ecological Transition & Environmental Management. He also specialises in European issues, including Cohesion Policy and Public Policy Evaluation. In his research, he combines quantitative methods, such as Spatial Econometrics and Modelling, with qualitative methods to offer a comprehensive perspective. Sébastien Bourdin has successfully led numerous research projects on contemporary subjects, including Renewable Energies and the Circular Economy.

![]() : Sebastien Bourdin

: Sebastien Bourdin ![]() : 0000-0001-7669-705X

: 0000-0001-7669-705X ![]() : Bourdin_Seb

: Bourdin_Seb ![]() : bourdinseb.bsky.social

: bourdinseb.bsky.social