Kantha, a traditional embroidered quilt from Bengal (now divided between Bangladesh and West Bengal, India), historically represented women’s domestic artistry through distinctive running stitches and colored motifs on layered muslin garments. There is a growing demand for commercial Kantha textiles in conditions of the ‘market,’ driven primarily by NGO setups (Modak, 2021). These ‘marketable Kanthas‘ emerge under the guidance of designers or cultural enthusiasts, marking a shift from the ‘usual‘ domestic production. Through a two-year ethnographic study of artisans, makers, and entrepreneurs, this research examines how ‘choice‘—the interplay between buyers’, designers’, and artisans’ preferences—shapes contemporary Kantha production. The study reveals how monetary involvement influences gender roles, thematic choices, techniques, materials, and artisan-designer dynamics.

Domestic Embroidery

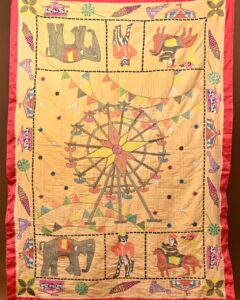

In the context of women’s embroidery within the domestic, Classen (2012) accounts for women’s duty of decorating the household as ‘crafty ladies’ in 17th-century Europe. Similarly, Walsh (2004) addresses decorative embroidery as a fundamental domestic duty for women in Colonial Bengal. During fieldwork, embroiderer Dolly Paul described kantha’s dual role: as domestic utility and ceremonial gifts (‘dan’) to brides (Fruzzetti 1982, Borthwick 1984). On the other hand, Ahmad (1997, 2009), Zaman (2009), and Ghosh (2020) have informed the multiple purposes of kantha generationally made by women in rich with the visuals (Figure 2) of their livelihood in the context of contested socio-political situations in modern-day West Bengal and Bangladesh.

Considering these, Kantha is referred to as the prevalent process of decorating, repairing, and mending, which is women’s responsibility within the domestic for familial purposes. It further accounts for women’s position in domesticity, unpaid care work, and association with embroidery. In modern life, social mobility and the changing mode of domestic involvement of women no longer produce Kantha as they used to. However, under the structured systems, with monetary benefits, it is getting created in a new mode through a particular transition within the growing larger craft market. Gradually, it enters the discourse of male embroiderers, bringing the case study of Pinaki Guha’s Kantha project with monetary involvement. In this case, as part of the discourse of domesticity and femininity, I would assess the socio-cultural role of embroidery by referring to McBrinn’s (2021) account of male embroiders and the gendered panic.

On Production

McBrinn (2021) brings attention to the conditions of male embroiderers and the social production of images in the context of late twentieth-century America and notes,

‘The male needleworker was also marginalized in the increasingly professionalized and commercialized craft industries that perpetuated Victorian notions of needlecrafts as domestic and stereotypically feminine.’

Simultaneously, Kantha embroidery has always been an interior decorative feminine enactment unless it is ‘responsible for the financial support.’ I argue that the practice of embroidery in the Indian context, sitting and doing as leisure or domestically, which has no monetary benefits, is still considered feminine; however, in professional ‘production,’ it is not. This identifies and addresses Kantha’s material cultural mobility.

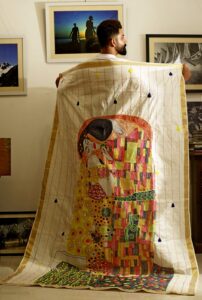

I propose Pinaki Guha’s project, which represents a significant shift in Kantha production through its collaboration with Nizamuddin Mallick, a male embroiderer from Bishnupur. Mallick’s professional background in the Mumbai film industry brings new expertise to this traditionally feminine craft. Simultaneously, Guha is a high school teacher in West Bengal who is ‘aware’ of the needs and tastes of Kolkata-centric urban consumers. Guha has also informed us that they are approaching a process that is ‘quick’ and ‘tasteful.’ So far, artisan Nizamuddin uses a particular setup to produce kantha with aari work in new fabrics instead of running stitches in used clothes. Under Guha’s direction, the project reinterprets kantha through reproductions of acclaimed artworks, from Klimt’s ‘The Kiss’ to traditional Gond painting and museum pieces (Figures 1, 3, 4). This approach reidentifies kantha from domestic craft to commercial art.

Of Market

Referring to the embroidery practices as ‘masculine,’ McBrinn (2021) notes that reproducing well-known paintings is ‘serious’ as it could drive beyond the status of ‘decorative.’ The ‘decorative’ denotes the obvious effeminacy of women’s embroidery work as ‘crafty ladies’ in decorating the household for non-commercial purposes. However, Guha’s project involving male embroiderers represents kantha as more ‘serious’ and ‘designed.’

Since the entry of male embroiderers with a specific monetary involvement, there has been a significant transformation in themes, process, character, and material practice, with entirely new fabrics, techniques, and stitches to serve the larger urban craft market. So far, reproducing acclaimed themes has made it distinctive and neo-exotic, able to attract urban consumers. On the other hand, domestic kantha (Figure 2) is filled with more mundane visual vocabulary. Eventually, my argument establishes that kantha is between ‘self-use’ and ‘of the market,’ having a crucial perceptual transition from kantha made for domestic purposes by women as amateurs to kantha produced for the market by men. However, the ‘usual’ domestically produced kantha is in an ideological shift when a crafts ‘man’ would work ‘professionally/commercially’ by ‘choice’ of designer and the market as the ‘production’ of embroidery of ‘marketable Kantha.

References:

Author

Kaustav Chatterjee is an art practitioner, writer, and researcher in Visual Arts and Cultural Studies who completed a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) from the University of Hyderabad, India. Kaustav is currently employed as a researcher in art, art history, and archaeology with the Pleach India Foundation Hyderabad.

Kaustav’s research, practice, and writing focus on colonialism, kinship, care, labor, and exploring through painting, drawing, textiles, and video works. Kaustav has been writing on mercantile crafts and transnational material histories of South Asia, involving publication projects on Banarasi textiles, embroidery practices, and sugar crafts of India, simultaneously formed an independent research project that deals with exhibition and exhibition making and critical writing on intersectional approaches to art/craft knowledge systems, sensorial practices, religion, community cultures, in-between theory and practice, archival studies, design studies, art/craft histories, anthropology, archaeology, and the history of science.

Connect with Kaustav:

Email: kaustav.c.now@gmail.com