Environmental politics face undeniable challenges. Despite decades of international agreements, key targets like emission reductions and biodiversity conservation remain unmet. With six of seven Earth-system boundaries transgressed and societal resistance growing over energy security and rising living costs, the dominant approach is failing. A shift toward “eco-social” politics is urgently needed.

The Limits of Environmental Liberalism

The dominant environmental politics paradigm, often called “environmental liberalism,” relies on market-driven solutions and technology. Rooted in a nature-society dualism, this paradigm frames environmental issues as “externalities”—errors in pricing that can supposedly be corrected without fundamentally altering the systems of production and consumption that generate them. This ignores the reality that cost-shifting—offloading costs onto others for private benefit, for example, through exploitation and appropriation—is intrinsic to capitalist economies. Without cost-shifting (aka “externalities”), capitalism cannot function.

Simultaneously, solutions like electric cars and passive single-family houses promise a more efficient continuation of business as usual, while carbon capture and storage technologies aim to capture and store carbon out there, and geoengineering aims to change the world around us so that we do not have to change. Ultimately, relying on pricing and technological fixes sidesteps the necessary transformation of social practices and capitalist relations.

Overcoming the Nature-Society Dualism: The Case for Eco-Social Politics

Eco-social politics dismantles the dualistic thinking that separates environmental issues from social ones. It recognizes that environmental problems are not external to society but the result of society-nature relations and their underlying tendencies, including capital accumulation, commodification, cultural norms, and inequalities.

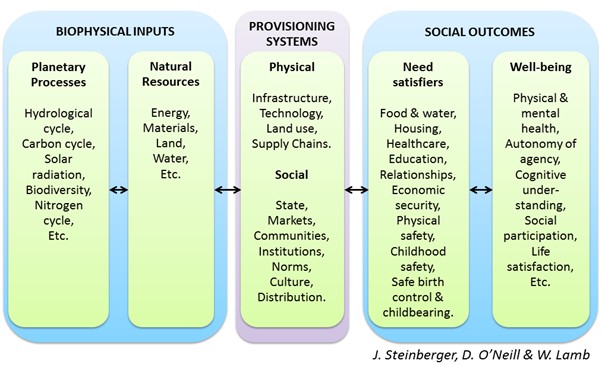

As such, eco-social politics focuses on the transformation of provisioning systems, which mediate the relationship between society and nature (see Figure 1). Provisioning systems—such as housing, food, energy, and transportation—are networks of material, infrastructural, socio-cultural, and political-economic elements that shape how we live, produce, and consume, as well as “who gets what, how, and why.”

Sufficiency: The Strategy of “Enough”

Central to eco-social politics and to provisioning systems research is the concept of sufficiency, a strategy of “enough.” While efficiency—using fewer resources per unit of output—is necessary, it is insufficient, as efficiency gains often lead to increased production and consumption.

Sufficiency prioritizes absolute reductions in resource and energy use while ensuring equitable access to essential goods and services. For those in poverty, “enough” means “more,” while for resource-intensive groups, it requires “less.” Sufficiency is not about individual lifestyle changes but a societal shift requiring infrastructures, regulations, and institutions that prioritize collective well-being over individual excess.

Building Alliances

Eco-social politics challenges the elite bias in environmental policymaking, which prioritizes high-status groups due to their ability to pay for green products and openness to technology narratives. Ironically, these groups, with the largest ecological footprints, are framed as drivers of transformation, while low-status groups are labeled as opponents (e.g., here). This reasoning also emphasizes clearer communication of environmental policies to “educate” low-status groups but fails to grasp that simplifying the language of elitist politics does not change its underlying form or content.

In contrast, eco-social politics emerges from and empowers lower-status groups, aligning with their material interest in achieving a social-ecological transformation aimed at “enough.” These alliances focus on equitable access to foundational systems like housing, healthcare, and energy, addressing the needs of disadvantaged communities. While environmental liberalism often struggles with people prioritizing immediate concerns, like social security, over “environmental issues,” eco-social politics integrates these concerns as core to its agenda. From this perspective, what environmental liberalism labels as “co-benefits”—such as sustainable development or improved health—are not side effects but central to the political vision itself.

The core challenge in forming new alliances lies in demonstrating that decent living conditions for all require limiting overproduction and overconsumption, linking “not enough” with “too much.”

The Example of Housing

Housing illustrates how eco-social politics can tackle both environmental and social challenges. Current strategies often prioritize new construction, fuelling biodiversity loss and carbon emissions. Going beyond eco-reductionist critiques, eco-social politics demonstrates how growth-driven housing systems are also socially harmful, impacting the lived realities of many.

For example, it emphasizes that addressing housing needs requires radically curbing excessive practices like financialized housing production and second-home ownership, which inflate land prices, raise rents, and worsen housing shortages. Growth-driven housing systems also undermine social well-being, contributing to deteriorating town centers and higher living costs due to car dependency. Additionally, while private homeownership is often promoted as a ‘smart’ solution for old-age housing within an asset-based welfare framework, it disregards the lived realities of older people, frequently exacerbating social isolation.

Eco-social politics, therefore, acknowledges the need for retrofitting and constructing energy-efficient housing but moves beyond these efforts, prioritizing systemic changes to housing provisioning. These include de-commodifying housing, regulating excessive living space, enhancing collective living environments, and fostering norms, skills, and programs for multigenerational and shared living.

Unlike environmental liberalism, which relies on technology, price adjustments, and growth to address social ills, eco-social politics problematizes the production, use, and distribution of the existing housing stock. Producing energy-efficient homes that remain vacant, serve as financial assets, or contribute to sprawl and social isolation wastes resources and deepens social-ecological crises.

This blog post draws from a forthcoming chapter in the SAGE Handbook of Eco-Social Policy and Politics and was presented at the 2024 RSA Winter Conference.

Author

Richard Bärnthaler is an Assistant Professor/Lecturer in Ecological Economics at the Sustainability Research Institute, University of Leeds, UK, where he co-leads the Economics and Policy for Sustainability research group. He also serves as a board member of the European Society for Ecological Economics, an Associate Editor at Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy, and a lead author for the Austrian Panel on Climate Change (APCC).

Connect with the Author:

![]() : @rbaernthaler.bsky.social

: @rbaernthaler.bsky.social ![]() : richard-bärnthaler

: richard-bärnthaler ![]() : 0000-0003-3595-2127

: 0000-0003-3595-2127