When thinking of China’s primary economic prowess, the country is often thought of as ‘the factory of the world’ – global products such as clothes and electronics have labels of ‘made in China’. What is perhaps much less known is that China has produced numerous world-leading infrastructure projects, including the world’s fastest passenger trains, longest highways, tallest skyscrapers, and largest hydropower station.

Bullet train in China taken by ABCDstock © Shutterstock

Imagine China has extended its domestic infrastructure revolution out into the world on an unprecedented scale with both a transcontinental and a trans-local reach. China has done exactly this through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013. Over eight short years, the BRI has unleashed an’ infrastructure storm’ carrying waves of overseas construction including cross-border freight and passenger trains, large hydropower dams, high-voltage power transmission lines, special economic zones and fibre optic cables, as well as municipal infrastructure like city roads, light rail and sewer systems particularly in parts of Asia and Africa.

Much of the provision of China-driven global infrastructure has occurred along the BRI’s six cross-border economic corridors and their sub-corridors. It has led to a new round of corridor-shaped or elongated and ‘extensified’ regionalisation, which in turn affects the existing patterns of globalisation, urbanisation and economic development. My new book, supported by a RSA Policy Expo grant (also involving Julie Miao and Xue Li), explores these interconnected global-regional-local processes.

The BRI’s far reach and strong impact

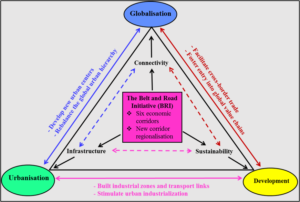

Any regional development, especially the kind that spans national borders, has both global and local dimensions. While not entirely new, this round of corridor regionalisation, fueled by the BRI’s numerous connective infrastructure projects, drives a new round of regional formation and transformation. My book advances a broad framework for analyzing how these dynamics play out and with what consequences (see image below).

Created by author – originally published in Chen et al., 2020

Through this framework, I argue that the BRI-induced regional development is the new driver of connections and interactions with globalisation, urbanisation and development, respectively. This driving force works through connectivity to link some landlocked countries and small and remote cities largely unconnected to the global economic network. This driver also shapes urbanization through new infrastructure projects like industrial zones for strengthening marginal cities and cross-border railways that connect them to other urban centers into extended industrial agglomeration.

The BRI creates new opportunities for more sustainable economic and social development in the Global South via the local embedding of such industrial or logistical assets as factories and transport facilities, both of which had sustained China’s own development through the early 2000s.

To explore the BRI’s regional impact on globalisation (Chapter 2), I have focused on the China-Europe Freight Train (CEFT) as an expanding set of transcontinental freight routes that have fostered new and redirected existing trade flows between China’s coastal cities and Europe’s Atlantic shore with many countries and cities across Eurasia. Among these routes is the world’s longest freight train run between the Chinese city of Yiwu (near Shanghai) and Madrid, covering eight countries over 13,500 kilometres. Using one route, a large manufacturing company based in Huizhou, southern China has improved its supply chain management by shipping parts to its factory in Zyrardow, Poland in much less time than by sea. By increasing the cost effectiveness of long-distance logistics, the CEFT helps reorganize global trade and production networks.

Chapter 3 has examined the combined role of new cross-border special economic zones and the China-Laos Railway from Kunming to Vientiane to be opened in December 2021. This zone-rail combined corridor is beginning to create favorable conditions for faster urbanisation and industrialisation along the transport artery that opens an access for landlocked Laos and China’s Yunnan province to export by sea through Thailand.

In Chapter 4, I have investigated the Djibouti-Ethiopia development corridor anchored to the China-built Djibouti Port and Djibouti International Free Trade Zone and connected by the China-built Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway, which opens a pathway to sea for landlocked Ethiopian exports from a number of special economic zones, some of which also involve Chinese investment. This cross-border regional corridor not only has turned the strategically located Djibouti into a new and influential logistics hub serving the broader East Africa but accelerated Ethiopian export-oriented industrialisation that can benefit from faster shipping to international markets via Djibouti Port.

Can the BRI be both a regional and global public good?

Through three case studies of China’s corridor-shaped infrastructural footprints in Europe, Asia and Africa, I have captured the BRI’s far reach and strong impact regionally and globally. In the last chapter, I raise the critical long-term question about the BRI: can its generally valued goal of building infrastructure drive it from a single-country, well-intentioned initiative to a synergistic force? If yes, the BRI will foster the production and delivery of regional public goods suited to the scale and length of its corridors. If the BRI-induced regional public goods that materialised over time, they can sum up and spread out as global public goods anchored to a wider extension and distribution of productive infrastructure led by China – a positive scenario for both China and the world.

For more information, please see:

Reconnecting Eurasia: a new logistics state, the China–Europe freight train, and the resurging ancient city of Xi’an (Eurasian Geography and Economics, published online on September 17, 2021)

Connectivity, Connectivity, Connectivity: Has the China-Europe Freight Train Become a Winning Run? (The European Financial Review, August/September, 2021).

“Built by China” Going Global (The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, December 2, 2021)

Is the Newly Operational China-Laos Railway a Game-Changer? (The European Financial Review, Feb. 16th, 2022)

Xiangming Chen is Raether Distinguished Professor of Global Urban Studies and Sociology at Trinity College in Connecticut USA and a visiting professor at Fudan University in Shanghai. He has published extensively on globalisation and urbanisation with a primary focus on China’s cross-border connections to other regions of Asia and the world (Homepage). Contact: xiangming.chen@trincoll.edu.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.