The aim of smart specialization is to support regions in building on their existing strengths to develop competitiveness in related, but more complex, new activities. So why do regions often target other types of activities in their smart specialization strategies? The full paper on which this blog is based on is available here.

Since 2014 smart specialisation has become the central approach to both regional innovation and cohesion policy in Europe. In the 2014–2020 program for the European Structural and Investment Funds, access to EU funding became conditional on regions having a smart specialisation strategy. The objective was that it would lead to the launch of 15,000 new products to market, 140,000 new start-ups and 350,000 new jobs by 2020. This was to be achieved by an investment of 67 billion EUR to support the over 120 smart specialisation strategies developed by regions in Europe.

Smart specialisation is rooted in a notion of place-based innovation policy. It’s characterised by the identification of strategic areas for intervention based on an analysis of the strengths and potentials of a regional economy. However, there have been few evaluations of the efficacy of this prioritisation process. In our recent study, we examine the priorities in the 120 regional smart specialization strategies hitherto developed.

The evidence reveals a rather mixed bag of approaches, many with little potential for smart specialisation to have a transformative impact on European regions.

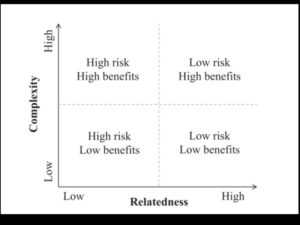

A large body of literature recommends regions to target activities that are complex and that are related to their existing strengths and competences. A straightforward visualisation of what this looks like is provided below in Figure 1, from Balland et al. (2018). In our study, we translate this into an empirical assessment of regional smart specialization strategies. That is, we examine the complexity of economic activities regions prioritized in their strategies and also measured their relatedness to the region’s current competitive strengths. This allows us to better evaluate whether regions were a) selecting domains which they were likely to be successful in (i.e. domains which are related to what they do), and b) selecting domains which are likely to be beneficial to a region’s economy (i.e. those domains which are complex).

Figure 1: Framework for Smart Specialisation (Balland et al., 2018)

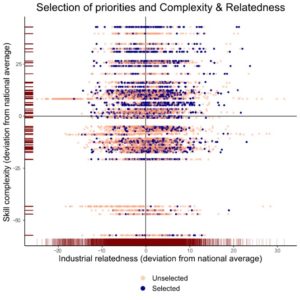

This is not what we observed in the smart specialization strategies developed by European regions. Figure 2 shows how regions’ priorities map onto the framework for smart specialization. Accordingly, from a European perspective, many priorities actually fall into the upper right quadrant, i.e., they show relatively high values of complexity and tend to be related to existing regional strength (see Figure 2). However, taking the perspective of the individual region, they were not chosen because of this combination. More often than not, regions selected economic domains that are either related or complex, but they hardly chose those that simultaneously excel in both dimensions.

Figure 2: Relatedness and complexity of economic domains in EU regions and the selection of priority economic domains

Consequently, our study suggests that regions in Europe may in fact be selecting domains which are unlikely to lead to a considerable improvement of their economic situation. Furthermore, we also find fashionable national policy seem to influence what strategies actually emerge as regions in the same country often select the same priorities, contrary to the place-based ideals of smart specialization.

This reflects a considerable discrepancy between the theoretical ideals and the practical implementation of smart specialisation. We can only speculate about the reasons for that. Maybe, it is a lack of solid data and tools to aid regions in their selection process, which facilitates the ad-hoc identification of priorities based on intuition and anecdotal evidence. Such a situation produces regional priorities which are poorly targeted and unlikely to stimulate innovative activity or indeed to produce sufficient economic growth in those regions which are lagging. Alternatively, it might have been an insufficiently clear formulation of the intentions behind smart specialization, which is even highlighted in its name, as smart specialization is conceptually more about diversification than specialization.

This raises another important question of whether the EU’s flagship regional innovation and cohesion policy framework can deliver on its objectives to promote diversification and upgrading of regional economies in Europe. This is a pertinent question as we enter the next programming period of smart specialisation (2021-2027). If smart specialisation is going to meet its objectives, the future implementation of the programme has to provide regions with better guidance and tools to identify suitable targets for the development of new competitive strengths.

Jason Deegan (Twitter: @jason_deegan) is a PhD student and research fellow at the University of Stavanger. His research primarily focuses on; Innovation, Regional Studies, Smart Specialisation and Policy.

Tom Broekel (Twitter: TBroekel) is Professor in Regional Innovation at the University of Stavanger Business School, Norway. He is also associated to the Center of Regional and Innovation Economics of the University of Bremen, Germany.

Rune Dahl Fitjar (Twitter: @fitjar) is vice-rector for innovation and society and professor of innovation studies. He has a PhD in political science from the London School of Economics from 2007 and has worked at UiS as a professor since 2013 and as vice-rector since 2019

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.