This blog was originally published on the Bennett Institute for Public Policy website and has been reproduced with permissions from the authors.

This blog follows the release of the book Levelling Up Left Behind Places: The Scale and Nature of the Economic and Policy Challenge by Ron Martin, Ben Gardiner, Andy Pike, Peter Sunley and Peter Tyler (Routledge), 2021.

Since it was elected in 2019, winning many northern constituencies formerly held by Labour, the UK Conservative government has made repeated pledges that it intends to ‘level up’ economic prosperity and opportunities across the country’s cities, towns and localities. As testimony to its commitment to that objective, it announced a Levelling Up Fund, renamed a major Government department as the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Community, and a White Paper on Levelling Up is imminent. Can the Government deliver on its pledge?

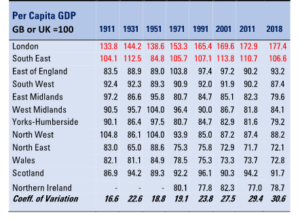

Regional economic inequality has long been a feature of the UK. Over the past century, formerly industrial regions such as the North West and West Midlands have fallen behind as London has increasingly pulled ahead (Table 1). We argue in our new book, Levelling Up Left Behind Places: The Scale and Nature of the Economic and Policy Challenge (Routledge), that nothing less than a bold new mission-oriented policy is required if geographical inequalities in economic prosperity and performance across the UK are to be significantly reduced.

Table 1: The UK’s spatially unbalanced economy

Employment Growth Output Growth

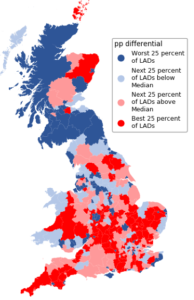

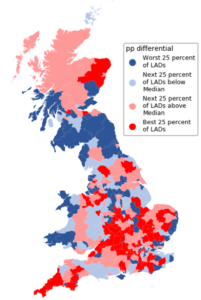

Figure 1: Cumulative differential growth of employment and output (GVA, £2016 prices), 1981-2018, for Local Authorities, by quartiles

Although the problem is in broad terms a regional one, it is at the local level that inequalities have widened considerably over the past four decades (Figure 1). Three key points are worthy of note.

First, slow growing or ‘left behind’ places can be found in every region. However, second, most of these are in northern Britain. And third, there are different types of ‘left behind’ place – old industrial towns and cities, isolated towns and small cities, rural areas, and coastal towns, some former tourist resorts, others fishing ports, others former naval centres.

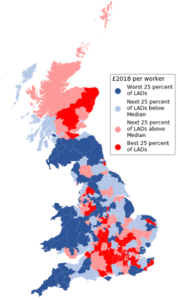

Much of the political concern over levelling up has centred on reducing the substantial disparities in productivity across the country. Again this is primarily, but by no means exclusively, a problem of northern cities, coastal areas and rural localities. There is considerable debate over why productivity differs so substantially across the regions, cities and localities. Our studies found that differences in economic structure and specialisation go only some way in accounting for uneven productivity. Further, it is far from clear what one is measuring in attempting to compare aggregate productivity between places, in part because it is the outcome of quite different output and employment dynamics from area to area.

Local Authority Districts, 2018, by Quartile

Figure 3. Labour Productivity (GVA per Employed Person),

A key question is why, after nearly a century of some form of spatial policy (regional policy dates back to 1928), geographical economic inequalities are still so pronounced across Britain. We identify several limitations and weaknesses of post-war policies; all have contributed to a disappointing impact of spatial policy over the past sixty years. These limitations include:

- Lack of recognition of scale and importance of the ‘left behind’ problem

- Insufficient resources committed to the problem

- Lack of a strategic vision for a spatially balanced economy

- Failure to take a holistic view of local economic development

- Failure to integrate regional policy with mainstream policymaking

- Overcentralised (‘top down’) approach to policy formulation and implementation

- Over-emphasis on ‘one-size fits all’ policy measures

- Disruptive churn of policies and policy institutions

- Inadequate development of local policymaking capacity and capabilities

Successive Governments have failed to fully recognise the scale and importance of geographical economic inequalities. This has been reflected in the limited scale of financial resources devoted to solving the problem. We estimate that from 1961 to 2020, there was an annual spend of £3.5 billion, equivalent to 0.15 percent of 2020 Gross National Income (GNI). Regional aid from the European Union added around another £1.4 billion (2020 prices) per annum. In combination, then, spending on urban and regional policy has amounted to about £4.9 billion per annum (0.27 percent of 2020 GNI). This is the size of the new Levelling Up Fund (which is not all new monies). It compares to £14.5 billion spent on international aid in 2019. Even more striking, it compares with a massive €2 trillion of aid and assistance (approximately equal to £55billion per annum) Germany has spent since 1990 on its Aufbau Ost programme to level up the East Germany economy with that of West Germany, post-unification. And, interestingly this latter sum is what Lord Heseltine, in his No Stone Unturned report (2012), is the scale of central Government spending that should be devolved to the local level across Britain.

At the same time, post-war spatial policy has been overly centralised from London as too top down and often ‘one-size-fits-all’ in character. And rarely, if at all, has spatial policy been properly integrated with mainstream national policy. Some aspects of this have benefited the more prosperous parts of Britain more than the left behind areas, and thereby, in effect, has acted as a ‘counter-regional’ policy.

If levelling up is to succeed, it requires a major departure from past spatial policy thinking and practice. We are at an historical juncture where the Government’s aim to ‘build back better’ from the COVID-19 pandemic and to achieve the transition to a net zero carbon economy can afford a major opportunity to seize the moment. They should use these missions to invest in left behind places to achieve a more equitable distribution of good quality jobs and prosperity. Several fundamental principles will need to be in place to underpin such a mission-orientated levelling up policy (Table 3).

Table 3. Some key pillars of a mission-oriented Levelling Up Strategy

| Re-envisioning the economy

|

Moving beyond ‘nation as economy model’, to one in which every region, city and town is recognised as integral and essential to national prosperity

|

| Embedding geography into national policy-making | Evaluating regional and subregional impact of mainstream macro-economic policy-making, and ensuring those policies take explicit account of differing regional and local needs and priorities

|

| Setting clear legally-binding ‘levelling up’ targets | Specification of maximum acceptable spatial differences in key local economic indicators (such as employment rate, productivity, GDP per capita), and per capita equality in critical public services provision (such as education, transport, health)

|

| Establishing nation-wide devolved system of local economic development and governance | A federated territorial system of accountable city-region bodies/authorities, charged with delivering and monitoring holistic socio-economic development strategies

|

|

Binding commitment of financial resources appropriate to the task |

Legally binding central funding agreement, as a fixed percent of annual GNI, for local economic, social, infrastructural and environment schemes. Plus new system of Local Authority Economic Development (‘Leveling Up’) bonds; and regionalised Business Bank |

The first, and most fundamental, is to re-envision the economy. There is a need to move beyond a simple aggregate ‘national’ conception of the economy, to one founded on the explicit recognition that it is composed of individual communities, towns, cities and regions, wherein actual wealth creation, work, consumption, and public service provision take place. Put another way, every place matters.

This in turn means embedding geography explicitly into national policymaking, whereby national mainstream policies and spending programmes are evaluated to assess their regional and subregional impact and to ensure those policies take explicit account of differing regional and local needs and priorities. This necessitates, on the one hand, a mechanism by which local authorities can submit details of their needs and priorities to central Government, and, on the other, a requirement by each major Government Department to ensure its spending policies are consistent with the Government’s levelling up strategy.

As regards that strategy itself, there is a need to specify exactly what is to levelled up, where, and over what time period: that is, clear and binding targets will need to be established, so that progress can be monitored, and policies adjusted accordingly. Levelling up will not be a ‘one-off’ policy, nor one that can be accomplished over, say, just one parliament, and then wound down. It will require sustained policy: indeed, maintaining a spatially balanced economy should be a permanent foundational principle underpinning national economic management and policy.

Equally important, to succeed levelling up will necessitate a substantial decentralisation and ‘de-centering’ of the national political economy. The UK is one of the most centralised of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations in terms of economic governance. Recent moves to establish a limited number of combined mayoral authorities is a welcome move in this direction, but should be used to move to a nation-wide federated system of such city-region bodies, with the appropriate powers and resources. Comparison with Germany is instructive.

It is vital that such bodies should be properly financially resourced. Not only should there be a proper scale of central Levelling Up Funds available to local authorities, but also a devolution of central government spending where possible (of the sort and scale recommended by Lord Heseltine), and local city-region authorities should be enabled to construct their own financing models, raising funds from a variety of sources (including municipal bonds).

As we argue in our book, an historic change in spatial – and national – policy is now a matter of urgency if spatial economic inequalities are to be reduced. The urgency is not just economic in nature – though that would be grounds alone; the urgency is also political. Large and persistent spatial inequalities in economic prosperity and opportunity have become a source of social discontent and political disillusionment: even a threat to democracy. It is imperative that politicians seize the current unique opportunity to restore a sense of economic and social belonging across a post-Brexit, post-pandemic UK.

Professor Ron Martin is an Emeritus Professor of Economic Geography at the University of Cambridge, UK, and Emeritus Professorial Fellow of St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, UK.

Professor Peter Tyler is an Emeritus Professor of Urban and Regional Economics at the University of Cambridge, UK, and Emeritus Professorial Fellow of St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, UK.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.