This blog was written for the RSA Blog Student Summer Series that will highlight graduate student success in regional studies across the globe throughout the summer.

If the American West could be defined by one characteristic, it would be aridity. Water quantity and quality deficiencies perennially frame development controversies across the West– particularly in rural and agricultural regions which rely directly on water resources for their economic vitality. As climate change brings unprecedented droughts and as rural and tribal household water access issues go unresolved, technological solutions to rural water shortfalls seem more urgent than ever.

One answer is to drill wells deeper and pipe water farther, and roughly 30 Rural Regional Water Systems (RRWS) aim to do just that. Scattered mainly across New Mexico, Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota, the Systems serve tribal and non-tribal regions of up to 50,000 square kilometers through thousands of kilometers of pipeline, often connecting multiple small towns and thousands of households. In 2021, the Biden-Harris Administration funded RRWS development for $1 billion as part of broader legislative efforts to engender an inclusive and fair pandemic recovery through infrastructure investments in marginalized regions. However, if RRWS are to provide sustainable and equitable solutions to longstanding rural water hardships in the American West, their potential risks must be understood alongside their potential promise.

Risks and opportunities in RRWS development: the Musselshell-Judith Regional Water System

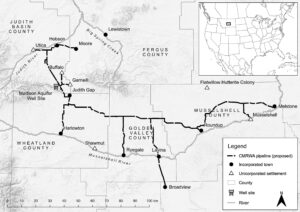

A recent study explored the challenges and opportunities of RRWS development through a case study of the Musselshell-Judith Regional Water System (figure 1). The proposed $90 Million, 500+ kilometer regional water system would provide clean and reliable water access to over a dozen small towns with longstanding histories of poor water quality and unreliable, ephemeral water sources. A key benefit of the proposed regional water system lies in its economy of scale: the towns which it serves–with populations between 25-900 residents–have historically struggled to develop the financial capital necessary to maintain high quality infrastructure systems, but by collaborating on a regional project, they can pool resources and reach a wider customer base. RRWS may allow under-resourced rural communities to build capacity and scale up, making higher quality infrastructure and public services more broadly accessible.

Figure 1

However, in its nearly 20-year history, the Musselshell-Judith Regional Water System’s organizational history also demonstrates that the proposal is unlikely to deliver universal drinking water access across the region due to pitfalls in its governance model. Because RRWS are regional in scope, their administration and management involves collaboration between multiple localities–bringing known challenges as local interests potentially clash with regional goals. For the Musselshell-Judith Regional Water System, what started as a collaboration between several small towns across the region has, in recent years, devolved into essentially a partnership between the two largest localities. The project lost participants as small towns slowly dropped out for various reasons: a key local leader passed away, another board member moved, one town dropped out because they didn’t have a representative to attend the meetings, and local political winds in another town shifted out of the RRWS’ favor.

In extremely remote and isolated contexts, where local civic leadership responsibilities are shared by a small group of people, the actions of key individuals potentially change the course of a town’s development trajectory–especially when hard infrastructure systems with lifetimes of several decades are the object of decision-making. Hence, without full representation, the grassroots governance model of RRWS risks giving way to uneven regional development outcomes as state-of-the-art RRWS facilities could serve some communities in the region while bypassing others.

Adapting to overlapping challenges

Like other large infrastructure developments, RRWS face complexities which go beyond the problems they ostensibly solve. The extent to which RRWS enable communities to adapt to overlapping environmental and governance challenges facing the rural American West will be highly contingent on local factors which vary from place to place. Successful RRWS management, like municipal drinking water management in rural regions, relies heavily on local capacities such as leadership potential and financial resources.

As regional and national leaders work towards implementing the Biden-Harris administration’s $2 Trillion national infrastructure investment, it is imperative that large scale infrastructure developments such as RRWS are inclusive in their governance and align with existing regional development plans. Doing so will be essential to ensuring national infrastructure investment priorities translate into equitable, regional-scale solutions to climate risks in rural areas with historic water challenges.

*Funding acknowledgement: This material is based upon work supported in part by the National Science Foundation EPSCoR Cooperative Agreement OIA-1757351, and United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture predoctoral fellowship proposal #2021-09489. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation nor the United States Department of Agriculture.

Grete Gansauer (Twitter @grete_rural) is a PhD Candidate at Montana State University.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.