The impacts of COVID-19 have been experienced unevenly: health impacts of the disease are well known to differ with greater risks associated with co-morbidities, including increased age and other vulnerabilities. The economic impacts are similarly diverse, with shocking intensity varying by groups: those from low-income backgrounds have been more likely to experience financial hardship, as have those from ethnic minority backgrounds, younger people, and renters. What has been less clear, however, is how geography – where people live – influences their individual financial experiences of the crisis and response.

We used data from the first three waves of the Understanding Society (UK Household Longitudinal Survey) COVID-19 study to investigate this. The UKHLS captures detailed information about people’s employment and financial situations, which we linked with contextual information about their neighbourhood (at lower layer super output area level) to consider the impact an individual’s local area has had on the financial impacts experienced through the pandemic.

Living in deprived areas was associated with poorer financial outcomes

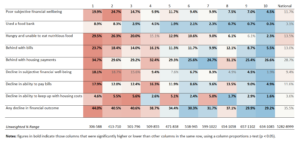

Our initial findings reveal clear social patterns: higher area deprivation is linked to poorer financial outcomes between May and June 2020, and a worsening of financial situations compared to pre-crisis situations (Table 1). For example, 18 percent of people living within the UK’s most deprived areas (decile 1) experienced a decline in their subjective financial well-being, compared to 2 percent of those in the least deprived areas (decile 10). 9 percent of those within the most deprived areas used a food bank compared with less than 1 percent of those in the most affluent areas.

Table 1 – Percentage of working age respondents in areas by deprivation decile (1 is most deprived) experiencing a negative financial outcome in one or more waves (April to May 2020).

Financial impact dependent on individual circumstance over neighborhood circumstance

To understand the extent to which these geographical patterns could be ‘explained’ by the individual and household-level characteristics of survey respondents we controlled for key factors including housing tenure, pre-COVID income, age and ethnicity. In doing so, we found that area-level variables added little to our models: whether or not people had been financially impacted by COVID-19 depended upon their individual circumstances prior to the pandemic as opposed to the contextual characteristics of place. In short, the social patterns observed are more likely to be the result of people with similar characteristics clustering together and living in the same places.

However, there are some exceptions. For example, those in London and those in Northern Ireland were more likely to have applied for Universal Credit (UC) than people elsewhere (after controlling for individual characteristics). We also found that people living within the most deprived areas of the UK were more likely to have made a new UC claim than those in non-deprived areas – but they were no more likely to have experienced other negative financial outcomes.

Certain groups face disproportionate financial impacts than others

Our study reiterates the variability of financial outcomes depended on group membership. This includes those living in social renting, from black ethnic backgrounds, those not born in the UK or employed on a non-fixed term salary, all of whom more likely to have experienced job loss than other groups. Having below degree level qualifications, being of ‘moderate’ clinical risk from COVID-19, or coming from a lower-income household were all related with an increased likelihood of furlough or accessing the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS).

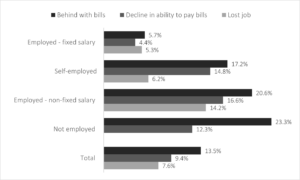

Work patterns prior to the crisis were also important in predicting financial difficulty. For example, those engaged in home working prior to the crisis were less likely to have been furloughed than those that have had to change workplace (19 percent compared with 31 percent). Those in insecure work (not on a fixed salary) were more likely to have lost their job than those on fixed salaries (14 percent compared with 5 percent) (Figure 1). Being self-employed or employed on a non-fixed salary and working in a COVID-affected industry were all factors associated with an increased likelihood of being furloughed or using SEISS.

Figure 1 – Percentage of respondents behind with bills, with a decline in their ability to meet bills or who lost their job, by pre-pandemic employment type.

What does this mean?

Our study has important policy implications. Firstly, we highlight individuals who may be suffering more financially as a result the pandemic, including social renters and insecure workers, indicating where government could target help.

Secondly, we identify the effectiveness of furlough and SEISS in mitigating hardship and the importance of post-pandemic financial support. Those furloughed were less likely to experience negative financial outcomes than those who experienced job loss, highlighting the importance of an efficient safety net. As Görtz, McGowan and Yeromonahos establish, although financial distress was higher for those who had been furloughed (compared to those remaining in work), lowering the furlough contribution to 60% would have doubled distress. They also indicate the 80% government contribution minimised the incidence of financial distress at the lowest cost to taxpayers.

Thirdly, our research reveals that individuals living in ‘left behind’, deprived areas are more likely to have struggled financially when compared to those in more affluent areas. Research by Brown and Cowling has similarly found poorer northern and peripheral urban areas of the UK experienced greater levels of business failure as a result of COVID-19 suggesting that targeted regional policies will be critical to mitigating the effects of the pandemic. This view is echoed in a blog by Martin and Tyler who emphasise the need to move away from a ‘national’ economy and recognise ‘every place matters’. They suggested embedding geography into national policy making and providing local authorities with appropriate resources and autonomy to enable successful ‘levelling up’. What is clear is that the pandemic has re-enforced pre-existing, long run, structural inequalities and targeted interventions in deprived areas are crucial for creating a more equal society going forward.

Katie Cross is a quantitative researcher working for the Personal Finance Research Centre, University of Bristol, UK. She conducts policy-relevant research across a range of areas relating to personal finance. She is particularly interested in research relating to poverty, inequality, financial well-being and living standards in the UK.

Jamie Evans is a quantitative social researcher at the Personal Finance Research Centre, University of Bristol, UK. His main research interests include financial inclusion, consumer vulnerability, and financial technology.

Julie MacLeavy is a Professor at the School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, UK. She has published widely on neoliberalism, austerity, welfare reform, and urban and regional policy concerns.

David Manley is a Professor of Human Geography at the School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, UK and Honorary Fellow at The Department of Urbanism in the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands. He has written extensively across urban and regional issues including inequalities, segregation and contextual effects relating to place.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.