This blog was written for the RSA Blog Student Summer Series that will highlight graduate student success in regional studies across the globe throughout the summer. Link to Original Article: Do EU goals matter? Assessing the localization of sustainable urban logistics governance goals in Norwegian cities.

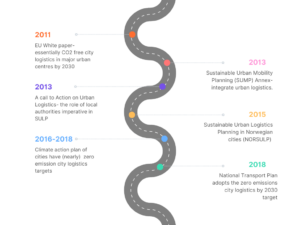

Urban logistics- the transport of goods and services in urban areas- is incredibly important for how cities function. In fact, urban logistics is embedded into our everyday lives. For context, try imagining the quality of life in a city where waste collection is halted, or department store shelves are empty. Urban logistics is also crucial to achieving the vision of healthy, livable, sustainable, climate-neutral cities- especially when we think about reducing transport sector emissions or traffic congestion. Surprisingly though, urban logistics has yet to be integrated into urban planning, as planning processes continue to be dominated by the movement of people. This lack of engagement is not only evident across cities but can also be traced at the European Union (EU) level. It was only in 2011- a little over a decade ago- that the EU explicitly recognized the role of urban logistics in urban planning and set an ambitious target of essentially CO2-free urban logistics by 2030.

Global and supranational goals, such as Sustainable Development Goals, climate targets, and sustainable urban logistics are developed at these higher levels. Nevertheless, they are implemented at the local level. This implies that global goals are adapted by cities according to their local-regional contexts, i.e., they are localized. But to what extent?

Tracing localization of EU goals in Norwegian cities

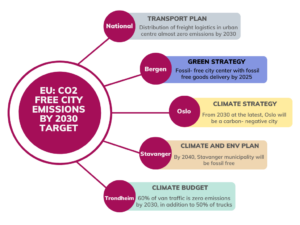

When we think of urban logistics, we tend to think of what happens within the boundary of cities. But new measures in urban logistics are not isolated decisions- these are shaped by external factors. The EU’s 2011 goal brought urban logistics into the radar of Norwegian urban planning. Following the call to action on urban logistics in 2013 by the EU, the Norwegian Roads Authority initiated a national project on sustainable urban logistics (NORSULP) in 2015 across nine cities. When we zoom in on four of these nine cities- Bergen, Oslo, Stavanger and Trondheim, we find that post NORSULP, these four cities have localized the EU goals to varying degrees. This localization is reflected in changing policy behavior across the cities over time. Yet it is more evident in some areas than in others.

On paper, the EU’s goal is effectively adopted. Two of Norway’s national transport plans (including the current NTP 2022-2030) have now explicitly included zero-emission city logistics in urban centers by 2030 as a target. Each city’s climate plan also has a target that (almost) matches the EU target of CO2-free city logistics goals. Cities have the tendency to discursively adopt such supranational goals- they are both easy and convenient- especially when they are non-binding. However, this does not guarantee that these goals will be met. Meeting these goals hinges on not only discursive adoption, but that it is simultaneously accompanied by changes in other policy behavior- resource, institution and relational changes.

Norwegian cities are yet to demonstrate such strong changes in other policy behavior. For instance, new actor relations, dedicated resources to ensure the goal is met, and institutional changes- from policy strategies to locally embedding the sector into current plans to changing current municipal practices- are difficult at the local level. Often, municipalities are already (severely) strained for resources (human and financial) and are likely to perceive such goals as one more addition to their otherwise already full plate. That said, the city of Oslo is doing relatively better than the remaining three cities- it is more forward in terms of integrating urban logistics into its institutional practices and municipal plans.

At the same time, Norway is yet to develop a national framework to ensure that the EU target will be met. For example, Bergen and Oslo had initiated groundwork on piloting zero-emission zones in their respective city centers- ambitious in the European context, where other cities had been developing low and ultra-low emission zones. But as there is no national legal provision for this, the two cities had to stall this initiative. Whilst this implies there is room for cities to learn from and collaborate with each other to localize EU goals of sustainable urban logistics, the extent to which this actually happens, in truth, depends on the national context.

Going full circle to answer, “to what extent?” – then the answer is that EU goals have been localized in Norwegian cities, insofar as the national level has facilitated this.

Food for thought

So, the next time we receive our next online purchase (hopefully on a zero-emission vehicle), perhaps it is worthwhile contemplating how deeply embedded urban logistics is into our everyday lives, and how this seemingly small practice of vehicle choice for delivery is, in fact, a culmination of goals set elsewhere.

Subina Shrestha (Twitter @iamsubina) is a second year PhD research fellow at the Centre for Climate and Energy Transformation at the University of Bergen, Norway. In her research, Shrestha explores the governance of urban transitions, with an empirical focus on urban logistics.

Funding: This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway [Grant Number: 308790].

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.