“Our island of Madeira is one of the essential and advantageous things that we and the crown of our kingdoms have for help and support. […] It seems just and necessary that said island […] should be the exclusive property of our crown forever.”

Through that letter (1497), Manuel I of Portugal asserted his sovereignty over Madeira, an island in the Atlantic Ocean located some 1,000 kilometers away from the mainland. How to enforce the crown’s sovereignty over a remote island territory? The colonization of Madeira was part of a power project. The crown initially envisioned a strong, dependent administration; nevertheless, the administration’s wide-ranging prerogatives became a means of autonomy from the crown.

The colonization of Madeira as a power project and the crown’s vision

Portuguese colonization commenced with the conquest of Ceuta in 1414, under a crusading spirit and mercantile power ambitions. For German economist Gustav von Schmoller, mercantilism is indeed a political project of nation-state power via trade policy. The crown organized two expeditions to Madeira (1419 and 1420) before deciding on colonization. Next, it sent settlers to populate the then deserted island and institutionalized a plantation economy (mainly sugar and cereals) based on mercantilism and slavery.

Prince Henry the Navigator (1394-1460) instituted an administrative structure by designing a system of captaincies (capitanias) and allocating land to his relatives. The “Letter of Donation” (“Carta de Doação da capitania de Machico a Tristão Vaz”) (1440) laid down the prerogatives of the king’s representatives, named captains (capitães-donátarios): judicial (execution of sentences), political (appointment of civil servants), economic (exclusive right to sell salt), and territorial (allocation of land). However, the crown rapidly observed instances of abuse of power from the captains and decided to reconcentrate administrative management.

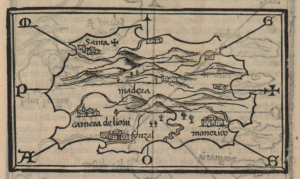

Original source here.

The gradual autonomy of local administrative staff

The crown transferred the captains’ prerogatives to local civil servants. For example, the almoxarife. who was originally a mere customs officer, gradually became responsible for monitoring all agricultural activities within the Royal Treasury (Fazenda Real). Insularity and remoteness constrained the crown’s interference; a local administrative elite emerged and sought greater autonomy. The gentlemen (homens-bons) – notables declared eligible for municipal posts (municipios were created in 1450) – are a case in point. Originally, declaring their eligibility was the king’s prerogative. Then, in 1616, the king deconcentrated it to two crown servants: the auditor (ouvidor) and the corrector (corregidor). The administration remained subordinate to the crown but, aided by distance, emancipated itself from it on the very basis of the extension of its prerogatives.

In Madeira, the Portuguese monarchy pursued a policy of economic and administrative strength. The failure of an administration decentralized to captains motivated a transition to a deconcentrated administration. The crown’s servants, even bound to the execution of royal orders, leveraged geographical distance and extending prerogatives for attaining sustainable autonomy. Today, in 2023, Madeira is an autonomous region (Região Autónoma da Madeira) with its own executive and legislative powers.

Coline Ferrant is an Assistant Professor in Social Development & Policy and Director of the Dean’s Fellowship Program at Habib University.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.