Francesco Aiello is Full Professor in Economics at the University of Calabria (Italy) where he teaches Political Economy and International Trade. He is an applied economist with a long dated experience in teaching and research and author of a number of papers published in referred journals in the fields of R&D, trade policy and development economics. In 2015, Francesco launched OpenCalabria.com, a website focusing on the regional economic divide in Italy.

Francesco Foglia is a Ph.D. scholar in Global Studies at the International University of Reggio Calabria in Italy and Research analyst interested in EU regional policy. Francesco holds a bachelor’s degree in Economics and a Master degree in Business Administration (with merit). His research on the evaluation of the European innovation policy was awarded by Jo Cox prize for European Studies (Economics). He is a co-founder of regional think tank OpenCalabria and professional journalist.

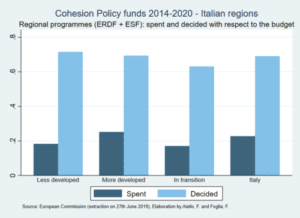

Considering the 2014-2020 EU programming cycle and only the European Social Fund (ESF) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the total amount of resources managed by Italian regions is equal to 35.5 billion of euro: 21.2 billion (approximately 60%) of these are allocated directly from the EU budget and 14.3 billion come from national co-financing.The Italian regions have spent a total of 7.4 billion of euro (4.6 billion of EU funds and the rest national funds) to date, representing 23% of the planned budget. Including the decided investments on the EU cohesion policy funds, this means that the Italian regions are finalizing interventions for a total amount of 25.8 billion of euro, i.e. 69% of the total regional programs.

Given the sequence that links the payments to the commitments, it is plausible to argue that the financial implementation of regional programs will continue on a regular basis, as the current commitments will contribute to new expenditures in the near future.It is noteworthy that current spending and commitments vary region-by-region.

In particular, the lagging regions (Basilicata, Calabria, Campania, Apulia and Sicily) record an expenditure that is, on average, lower than the national average (18% against 23%), while spending commitments reach 72% of their entire programming – 3% more than the national average. The regions in transition (Abruzzo, Molise and Sardinia) are below the national average both in terms of expenditure (17% of the regional program) and commitments (63%). The expenditure of the most developed regions (Emilia Romagna, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Lazio, Liguria, Lombardy, Marche, Piedmont, Tuscany, Umbria, Valle d’Aosta, Veneto and the provinces of Bolzano and Trento) reaches 25% of their total regional programming.

These data lead to a few of considerations.

Despite a slow start of the 2014-2020 programming cycle – which is a typical feature of all European programs – the regions have recently quickened the financial implementation of their Regional Operational Programs (ROPs), so that the spending targets certified at the end of 2018 have always been reached (with the exception of the ESF program in Valle d’Aosta). The achievement of these targeted objectives will allow some regions to even gain a financial incentive in the form of an additional grant, based on the Common Provisions Regulation (CPR) Regulation No 1303/2013.</br>

Other things being equal, these outcomes were possible because, after 25 years of EU planning, regions have learned how to use funds channeled through the ROPs: their capacity building has certainly increased over time. Furthermore, we do provide a basic empirical evidence to deny the mistaken popular perception that the Italian regions, and particularly those of Southern Italy, return resources to the EU: if all regions have so far used, on average, 23% of the resources made available by Brussels, this quota already exceeds 30% in many regional programs (for the ERDF in Emilia Romagna, Tuscany and Valle d’Aosta; for the ESF in Friuli Venezia Giulia, Lombardy, Piedmont and in the province of Trento). It is equal to 21% for lagging regions, 17% for transition regions and 25% for more developed regions. </br>

</br>

Figure 2. A comparison of planned and actual expenditures in Italian regions.</br>

Nonetheless, comparisons between regions must be interpreted with caution. Indeed, a ranking of the least and most virtuous regions in managing 2014-2020 EU funds is poorly informative because the programs are not concluded yet. Additionally, the amount of funds is different and, therefore, it is also different the number of procedures that need to be implemented in each region. In other words, it is easier to manage a relatively “small” program than a relatively “large” program; this is confirmed by the negative correlation (-0.25) that exists between (a) the share of each regional program on the national total and (b) the current expenditure of each region (in % of the regional total) (data refer to the end of June 2019).</br>

The main conclusion that can be drawn is related to the ability of Italian regions to respect the 2014-2020 expenditure timing, thereby not incurring in automatic de-commitments of EU funds. In this respect, financial performance is also good in Calabria, Sicily, Apulia and Campania, which receive and mobilize a large amount of resources: they absorb about 60% of the 2014-2020 regional planning in Italy.</br>

At the end of the story, we have learned that regions are spending and that the expenditure is done respecting the scheduled timing. However, it is not yet certain whether the current interventions will allow regions to pursue the development objectives that they fixed at the beginning of the programming cycle. Therefore, it also remains unpredictable if regional expenditure acts in favor of the aims characterizing the 2021-2027 programming cycle. The recommendation is to continue to spend, but being much more careful than in the past about the quality of the expenditure. In other words, spending is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a regional program to receive an ex-post positive assessment.

The authors wish to thank Alessia Via (PhD) for the translation.