This blog was written by Professor Anne Green and Rebecca Riley, City-REDI / WM REDI, University of Birmingham. To access the original article, click here.

The current situation in cities

The pandemic has changed the nature of work significantly which may have long term impacts. Not least is the fact that at a time when significant business decisions are being made, businesses have had a rapid shift to working from home. Reflecting back on the earlier piece on Cities in the monitor, the pattern of staying away from city and town centre continues, but there is significant variability between urban areas.

Remote working has seen a gradual increase over recent decades, with 1.5% of people in employment working mainly from home in 1981 rising to 4.7% in 2019. Evidence on recent trends in homeworking in the UK is available from a study primarily examining data from three online surveys undertaken in April, May and June 2020 as part of the Understanding Society: Covid-19 Study. This shows that nationally during the Covid-19 national lockdown in April 2020 43.1% of workers were working exclusively from home. In June 2020 the proportion had fallen back slightly to 36.5%.

Homeworking is positively associated with qualifications. The proportion of graduates reporting that they worked exclusively at home rose from 8.0% before lockdown to 62.4% in the first month of lockdown. By contrast, for those with no qualifications, the proportion exclusively working from home remained below 10% throughout lockdown.

A clear occupational pattern of homeworking is evident. In April and May 2020, a majority of those in managerial, professional, associate professional and technical, and administrative and secretarial staff worked exclusively from home. During the lockdown, those in associate professional and technical occupations and in administrative and secretarial occupations became more likely to be doing some of their work at home than managers. Only a small minority of those in elementary, operative and skilled trades occupations reported working exclusively from home at any stage during the lockdown. By region, employees in London became more likely to work at home taking into account all other characteristics and factors. By sector, there were marked differences in the extent of homeworking: three-quarters or more of workers in manufacturing and construction were not working from home.

In terms of prospects for returning to the office, it is particularly pertinent to examine who the ‘new home-centred workers’ are – i.e. those who did no work at home or did so only occasionally before the lockdown but reported working exclusively or often at home during the lockdown. Around a third of workers are in this category. They are predominantly higher qualified and better paid and more likely to be located in London and the South East. By contrast ‘established factory/office-centred workers’ who both before and after lockdown hardly ever worked from home (accounting for around half of workers) are lower qualified, more poorly paid, lower-skilled and more likely than average to be located in the Midlands, the North and in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

The table below shows trends in the use of the home as a workplace for workers in the West Midlands, where homeworking is slightly less prevalent than nationally (percentages shown in parentheses):

| Time | No use of home as a workplace | Use of home as a workplace – SOMETIMES | Use of home as a workplace – OFTEN | Use of home as a workplace – ALWAYS |

| Jan/Feb 2020 | 77.2% (70.6%) | 12.9% (17.7%) | 5.3% (6.1%) | 4.6% (5.7%) |

| April 2020 | 48.4% (39.5%) | 6.9% (9.1%) | 8.6% (8.3) | 36.2% (43.1) |

| May 2020 | 48.9 (40.0%) | 9.3% (10.3%) | 7.6% (8.9) | 34.1% (40.8) |

| June 2020 | 54.6 (45.3%) | 7.6% (9.6%) | 9.5% (8.7) | 28.4% (36.5) |

‘Enforced’ homeworking for some workers during lockdown appears to have given many employees an appetite for continued homeworking. In June 2020 88% of employees who had worked at home during lockdown reported that they would like to continue working at home in some capacity. 47% of employees wanted to work at home often or all of the time.

Return to offices – The West Midlands

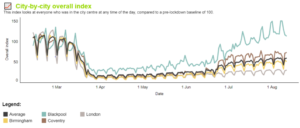

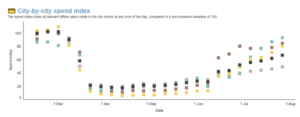

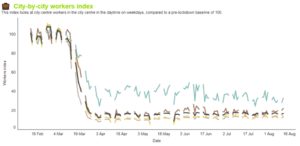

Returning to city centre offices is one element of the revival of city centre economies. The Centre for Cities has produced a recovery index showing footfall and spend in the daytime on weekdays, compared to a pre-lockdown baseline of 100. It should be noted that the index is partial as it is only selected areas and based on Primary Urban Areas, which also means that ‘Birmingham’ also includes Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull, Walsall and Wolverhampton and Coventry (without Nuneaton or Warwick) is its own area.

Looking at the top 10 places for footfall and spend some distinct characteristics emerge:

- Seaside towns where visits have remained higher, perhaps boosted by staycations

- Places which are the only local significant centre with a relative lack of competition from elsewhere

- Places with low levels of the sectors identified as ‘working from home’

- Places which had less of a drop in footfall throughout the pandemic

Looking at the bottom places for spend and footfall they share other characteristics:

- University cities and towns

- Higher % of knowledge workers

- Higher % of sectors identified as home working

Source: Centre for Cities

Source: Centre for Cities

Looking at the overall index and comparing the best/worst/average places and Birmingham and Coventry the pattern of weekend visits to seaside places versus the weekend drop in the city centre is evident, with a general slow increase of weekday activity. This also shows London has hardly changed from the height of lockdown. Birmingham remains below the average, but Coventry remains above the average.

Looking at the worker index for the same places, Birmingham remains significantly below the average (similar to London), with Coventry near the average.

Source: Centre for Cities

In terms of spending – Coventry after being below average in lockdown has now risen substantially above average, as has Birmingham. Whilst London still lags considerably.

Source: Centre for Cities

Homeworking and productivity

There is evidence to suggest that working from home does not have the negative impacts on productivity that some employers might fear. Results from a working at home experiment in 2013 amongst call centre employees at a Chinese travel agency, revealed a 13% performance increase amongst those working from home. (The experiment involved 1,000 employees who volunteered to be assigned randomly to two teams: one team working from home four out of five days for nine months and the other team working exclusively from the office.). Of the 13% performance increase, 9% was attributed to working more minutes per shift (due to fewer breaks, less commuting and fewer days off sick) and 4% from more calls per minute (due to a quieter working environment). It is important to note that the experiment was restricted to a sub-group of employees who met three requirements: having no children, having a room at home to work in that was not their bedroom and had high-quality broadband internet (i.e. conditions conducive to homeworking with limited disruption).

At the end of the experiment, the company rolled out a working from home option on a permanent basis. Interviews with those choosing to work from home at this stage revealed that half found working at home harder, as they became more isolated, while the other half were 22% more productive. This underscores heterogeneity in attitudes to working from home.

Evidence from the Understanding Society: Covid19 study in the UK found no significant reduction in productivity associated with homeworking during the lockdown. 41% of respondents working at home reported getting the same amount of work done in June 2020 as they did six months earlier. Similar proportions of homeworkers reported an increase (29%) and a decrease (30%) in productivity. Two-thirds of those reporting an increase in productivity wanted to work mainly at home in the future. Workers who spent all (as opposed to some) of their time working at home were most likely to report improved productivity, so supporting a business case for continued homeworking.

Communication

Research in the US has explored the impact of COVID-19 on employee’s digital communication patterns through an event study of lockdowns in 16 large metropolitan areas in North America, Europe and the Middle East. Using de-identified, aggregated meeting and email meta-data from 3,143,270 users, the research found, compared to pre-pandemic levels, increases in the number of meetings per person (+12.9 per cent) and the number of attendees per meeting (+13.5 per cent), but decreases in the average length of meetings (-20.1 per cent). Collectively, the net effect is that people spent less time in meetings per day (-11.5 per cent) in the post- lockdown period. They also found significant and durable increases in length of the average workday (+8.2 per cent, or +48.5 minutes), along with short-term increases in email activity.

So employees have expanded both their frequency and scope of communication. Larger meetings and email circulations appear to have led to a more inclusive approach to information dissemination. The nature of meetings has changed to reflect the missing office environment; the spillover effect, however, to more communication is longer hours worked.

A negative impact of homeworking is isolation and not feeling engaged; however, with a wholesale shift everyone is in the same position and proactive communication and engagement could help overcome this barrier.

Businesses will have difficult decisions to make as homeworking can reduce costs and potentially increase productivity, the two biggest concerns especially in a recession. There are also the corporate risks of bringing people back into an environment which may end in illness and quarantine, therefore reducing their workforce and bringing risks of litigation.

International evidence on the return to offices

International evidence suggests that the UK and the USA are returning to work more slowly and in lower numbers than in countries such as Italy, Spain, France and Germany. In part, the slower pace of return in the UK and the USA reflects the fact that the Covid-19 crisis hit later than in mainland Europe and harder.

A Morgan Stanley Research survey of 4,297 office workers undertaken in mid-July 2020 shows that in the UK at that time more than half of office workers surveyed would be either very (26%) or somewhat (29%) uncomfortable about hot-desking. The proportions uncomfortable with hot-desking were less than this in Germany, France, Spain and Italy. In the latter, the proportions who would be very or somewhat uncomfortable with hot-desking were 7% and 15%, respectively.

Another factor underpinning the slower return to the office in the UK and USA than in some mainland European countries is the sheer scale of cities such as London and New York and their reliance on public transport with its greater risk of contagion. Amsterdam is an example of a city that benefits from more alternative transport modes.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development, and want to elaborate your ideas in a different medium? The Regional Studies Association is now accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at RSABlog@regionalstudies.org.