Danny Dorling is the Halford Mackinder Professor in Geography at the University of Oxford. He was previously a professor of Geography at the University of Sheffield, and before then a professor at the University of Leeds. He previously worked at academic posts in Newcastle, Bristol, and New Zealand. He went to university in Newcastle upon Tyne, and to school in Oxford: Donnington, Wood Farm, Headington Middle, and Cheney Secondary school. He was born in 1968. His most recent 2018 book is ‘Peak Inequality’.

In hindsight we should have seen it coming. But none of us did, or at least no one who looks for the best in others.

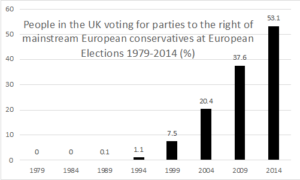

There was widespread shock when the electorate of the UK voted to leave the EU. They did this with a ratio of those who voted of 51.9 to 48.1. However, had we considered the graph below – a graph that could have been drawn as early as 2014, but was not – we might have been less sanguine and less surprised.

Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Parliament_election,_2014_(United_Kingdom). See also pages back to: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Parliament_election,_1979_(United_Kingdom)

The graph is a summary of the results of each European election that has been held in the UK since joining the then European Community in the mid-1970s. The first election was held in 1979 where the Conservatives won 48.4% of the vote and 60 of the then 81 seats available. No obviously far-right political party put up candidates. The group ‘United Against the Common Market’ did secure 27,506 votes, or 0.2% of all votes cast, but they appeared to be an across the board alliance. They did not put up candidates at the next European parliamentary election, held in 1984.

In 1989, the far-right National Front stood for the first time in an election and won 1471 votes, or less than 0.1% of the popular vote. By the 1994 election, the National Front increased their vote to 12,469 and UK Independence Party (UKIP) stood for the first time, gaining 150,251 votes or around 1.1% of the total vote. In the next European election in 1999, UKIP increased their vote to 696,057 supporters and the British National Party (BNP) stood in place of the National Front, securing 103,647 votes. The combined vote of the far-right climbed to 7.5%

After the millennium, in 2004, far-right voting in UK European elections jumped again, to 20.4% of all who voted. UKIP had become the third most popular party securing just by themselves 15.6% of the total vote, while the BNP also rose to become the fifth most popular party, securing 4.8%. The other parties began to take notice and, in particular, the Conservative party began to fear losing votes to these far-right alternatives, parties which advocated leaving the European Union.

At the next UK European Parliamentary election, held in 2009, I assigned half of Conservative votes to being to the right of European Conservatives in drawing the graph above. This is because the British Conservative and Unionist party position at that point was ambiguous, as they had withdrawn from the European Conservative bloc at the European Parliament, but had yet to align themselves with a new bloc. Thus, in 2009, 27.4% of the vote went to the Conservatives; UKIP got 16.0% of the vote, BNP 6.0%, English Democrat 1.8%, and a minor celebratory called Katie Hopkins won 0.1%. Half of 27.4 plus 16 plus 6 plus 1.8 plus 0.1 is 37.6.

By 2014, the UK Conservatives were allied with far-right parties in Europe and no longer at all associated with the main conservative European People’s Party block. By then the Conservatives were full members of a bloc of MEPs in the European parliament that was to the right of all traditional European conservatives. Summing up, in 2014 the Conservative’s had 23.1% of the vote, with UKIP’s 26.6%, the new ‘An Independent from Europe’ party’s 1.4%, the BNP’s 1.1%, the No2EU’s 0.8%, the new ‘Britain First’s 0.1%, resulted in a 53.1% vote for parties right of mainstream European Conservatives.

From then on, in hindsight, perhaps the writing was on the wall.

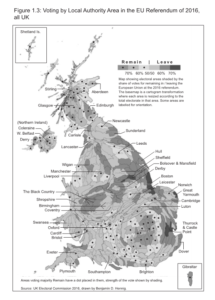

The map below shows the geographical outcome 2016

Danny Dorling is a plenary speaker for the RSA Winter Conference in London from November 15-16, 2018. The theme for the 2018 conference is New horizons for cities and regions in a changing world. The deadline to submit an abstract for the conference was August 20 2018.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development, and want to elaborate your ideas in a different medium? The Regional Studies Association is now accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at RSABlog@regionalstudies.org.