This blog was written for the RSA Blog Student Summer Series that will highlight graduate student success in regional studies across the globe throughout the summer.

The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally changed how and where we work. Rates of remote working skyrocketed during national lockdowns; for many, this was the ‘grand experiment nobody wanted’. However, remote working is now here to stay around the world, at least to some extent.

Remote working is changing workers’ daily and residential mobilities. In this blog, I analyse data from the UK Household Longitudinal Panel Study (UKHLS), an annual survey covering topics such as work and mobility, to illustrate how remote work is influencing counterurbanisation (residential migration from urban to rural areas) and commuting (daily travel to and from work). The data is sourced from Waves 10, 11, 12, and 13 of the UKHLS, corresponding largely to 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2022. Not all trends can be analysed pre- and post-pandemic because detailed questions on remote working were first included in the UKHLS in Wave 12.

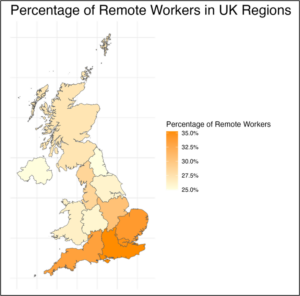

The latest UKHLS data from Wave 13 suggest that 68% of UK workers never remote work, while 32% remote work sometimes, often, or always. Hybrid working (working from home sometimes or often) is more common than fully remote working. Compared to non-remote workers, remote workers are more likely to be older, self-employed, and work in professional jobs. Remote working also varies across UK regions, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Source: University of Essex (2023). Map by author.

Counterurbanisation

The UKHLS data shows that UK workers have counterurbanised since the pandemic began. Between Waves 10 and 13, twice as many workers moved from urban to rural areas as moved from rural to urban areas. In comparison, urban-to-rural moves were only 1.4 times more popular than rural-to-urban moves in the equivalent period pre-pandemic.

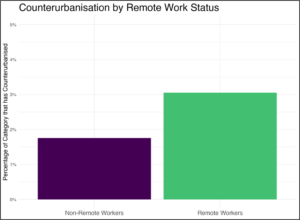

Figure 2 shows that 1.8% of non-remote workers relocated to rural areas, whereas 3.0% of remote workers did the same. This difference supports the notion, widely popularised in academic and media discourse, that remote workers may be more inclined to live rurally since they are no longer bound to traditional workplaces. Counterurbanisation has been more popular among those who remote work sometimes compared to often or always.

Figure 2. Source: University of Essex (2023). Plot by author.

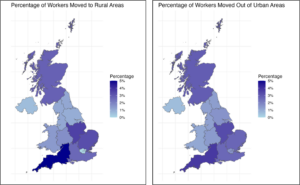

However, this trend has not been equally spread across UK regions. Figure 3 (left) shows the regions where most workers have left urban areas, and Figure 3 (right) shows the most popular destinations for counterurbanisers. The similarity in these maps may suggest that many workers have moved to a rural area within the region where they already lived.

Figure 3. Source: University of Essex (2023). Maps by author.

Commuting

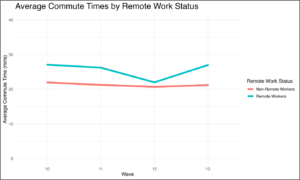

The UKHLS data shows that remote workers have longer commute times than non-remote workers. While remote workers’ average daily commute time is 27 minutes, non-remote workers’ average is 21 minutes. This supports studies that suggest remote workers often commute longer distances because they are willing to live further away from their work. However, the UKHLS does not provide data about how frequently workers commute; therefore, no conclusions can be drawn about total commute times.

Notably, neither group’s commute times have significantly changed since the pandemic – Figure 4 shows relative stability in commute times between Waves 10 and 13.

Figure 4. Source: University of Essex (2023). Plot by author.

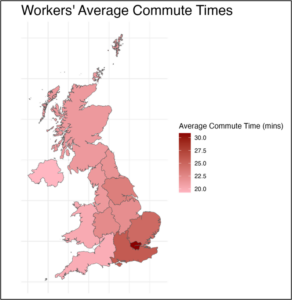

Commute times also vary significantly across the UK, as shown in Figure 5. Unsurprisingly, regions with longer commute times (i.e. London and the South East) have high proportions of remote workers.

Figure 5. Source: University of Essex (2023). Map by author.

These findings have important implications for community and regional resilience in both urban and rural places. In cities, workers leaving central business districts contribute to the ‘donut effect’, where suburbs and accessible rural communities become increasingly attractive places to live and work. This has created questions about the future of city centre offices and whether their function and structure should be rethought. These impacts are likely to vary across types of urban areas, with central agglomerations likely to remain more important in larger cities.

Remote workers are often more affluent than other rural residents, as they are often employed in higher-paid, professional sector jobs, creating concerns about counterurbanisation increasing house prices and exacerbating gentrification in rural communities. Others claim that counterurbanisers can stimulate rural development through entrepreneurship and investment. Additionally, as rural workers commute less frequently, they may spend more time and money in their communities. Further research is needed to fully understand the impact of these new trends in rural communities, where remote working remains understudied compared to cities.

As the most recent UKHLS data were collected in 2022, the long-term, post-pandemic nature of the findings presented here remains unclear. It will be interesting to examine the Wave 14 UKHLS data once they become available in November 2024 to identify whether these trends persist.

Kirsten Clarke is a first-year PhD student jointly based at the James Hutton Institute in Aberdeen and the Countryside and Community Research Institute at the University of Gloucestershire. Her PhD research examines the impacts of post-pandemic remote working on rural-urban mobility and community resilience.

Funding information: PhD jointly funded by the James Hutton Institute and the University of Gloucestershire

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.