Andrea Morrison is currently Marie-Curie Fellow at the Department of Management and Technology, Bocconi University and Associate Professor in Economic Geography at Utrecht University. His research interests lie in the areas of evolutionary economics, innovation studies, economic geography and economic development. He has investigated extensively topics like system of innovation, industrial clusters, knowledge networks, global value chain and the geography of science. More recently he turned his attention to international migration as driver of innovation and technological diversification. You can find him on Twitter at @morrisonXandrea.

Dario Diodato is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Center for International Development at Harvard University. Before his PhD in Economic Geography at Utrecht University (2013-2017), he was a researcher in urban and regional economics at the PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (The Hague, 2009-2012). His research interests lie in the area of technological change, structural transformation, migration and technology diffusion, cities and regions, human capital and skills, economic complexity and economic resilience.

Sergio Petralia is a postdoctoral researcher at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He joined the Center for International Development’s Growth Lab as a Visiting Fellow in 2018. Sergio is currently working on issues related to technological change and innovation. Most recent research projects study the emergence and spatial concentration of new technologies using historical data on patent activity and the identification of the challenges and opportunities for technological development in developing economies.

High skilled migration in the Age of Mass Migration in the US

In the last few decades the international migration of high-skilled workers has increased dramatically (World Bank, 2018). Despite the sheer size of the phenomenon and the obvious policy relevance, there is relatively little scholarly work investigating the link between migration and innovation (Kerr, 2013; Breschi et al. 2015). The link between migration and innovation is an important one though, as many of today’s and past most innovative US companies as well as scientific and technological discoveries can be traced back to foreign born entrepreneurs and scientists (Hughes 2004). More recently, also due to the backlash against immigrants in the US, this topic has regained popularity among scholars, who initiated a new research line on the economic impact of historical migration in the US (Abramitzky and Boustan, 2017).

With this project we contribute to this emerging literature by looking at a crucial event in American history, the age of mass migration: between 1860 and the mid-1920s more than thirty million people migrated to the US in search for a better life. Along with the millions of immigrants entering the US during these six decades, in the order of thousands were or became inventors and patentees. It is worth mentioning that inventive activity before the early twentieth century was primarily an individual endeavour, which required relatively little capital (Hughes, 2004). Moreover, the barriers to carry out an inventive activity were particularly low, patenting was attractive also for disadvantageous groups, including immigrants (Khan, 2005).

New data sources to unveil the geography of High Skilled immigrants in the US

To carry out our investigation we constructed a new dataset that identifies migrants in historical patent documents of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). These documents provide information about the citizenship of the patentee. Patent document in Figure 1 below provides a clear example. This patent shows an invention granted to Nikola Tesla, the great Serbian inventor. It is highlighted in this document that Tesla comes from Austria-Hungary and resides in New York. With this information at hand we were able to identify all inventors with foreign citizenship and American residents.

Figure 1. Example of historical USTPO patent document.

The geography of high skilled migrants in the US

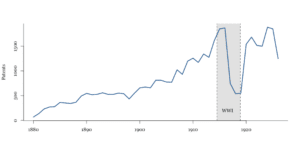

The first interesting finding of our analysis is that inventor migrants moved to US along with the big waves of the Great Migration. Indeed the growing trend in patenting observed from 1880 until 1916 closely resembles the flow of immigrants (see Figure 1). The peaks and troughs capture historical shocks, like WW1 (1914-1918) and the introduction of immigration quotas in the US (1924). After mid-1920s, there is a steady decline in immigrant patents, as for immigrants in general.

Figure 2. Patents of immigrant inventors in the US

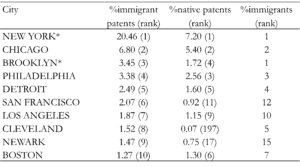

The geography of these talents also mirrors the distribution of ethnicities present in the US in those years. As shown in Table 1, the ranking of most prolific patenting countries reflects, to a large extent, the distribution of the immigrant population in the US, with Great Britain at the top of the list, followed by Germany. All other major European countries who experienced large flows of emigrants to US are listed. The geography of immigrant inventors in the US shows a well-known pattern of clustering. In particular, as immigrant in general in those days (Abramitzy and Boustan, 2017), and as immigrant inventors nowadays (Kerr, 2007), also immigrant inventors back then tended to agglomerate in specific large urban areas, like New York and Chicago (see Table 1).

Table 1. Clustering of Immigrant vs Natives inventors

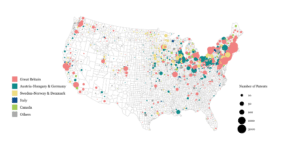

Moreover, the east coast of the US, which at that time was the core of American manufacturing industry, had a more prominent position (see Figure 3). Nonetheless, a not negligible number of patents appears also in the Mid-West, where large communities of German and Scandinavian immigrants were located.

Turning our attention to contribution of immigrant inventors, we explored to what extent these talented immigrants contributed to the ingenuity of US cities. Our findings show that both the total patenting, and in particular the patenting of natives, were positively associated with patenting of immigrant inventors in a given city, technological class and decade. These findings are well aligned with recent evidence of immigrant inventors in US cities (Kerr and Lincoln, 2010).

Implications

This project found that immigrant inventors had a twofold effect on the US inventive activity: a direct impact, as they patented their ideas,and in addition, they generated positive externalities, which increased the productivity of US native inventors. Extrapolating these results, we observe that these effects creates path-dependent knowledge accumulation at the city level. This implies that immigrants’ networks contributed to the formation of specialized innovation hubs in the US economy, and shows that, not too differently from today, that global talents tend to cluster in space and contribute to the expansion of the technological clusters where they settled down.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development, and want to elaborate your ideas in a different medium? The Regional Studies Association is now accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at RSABlog@regionalstudies.org.

References

Abramitzky, R., & Boustan, L. (2017). Immigration in American economic history. Journal of economic literature, 55(4), 1311-45.

Breschi S, Lissoni F, and Temgoua N C. (2015) Migration and Innovation: A Survey of Recent Studies. In The Geographies of Innovations: Beyond One-Size-Fits-All, Edward Elgar. Shearmur R.and Doloreux D., and Carrincazeux C., 2015;

Hughes, T. P. (2004). American genesis: a century of invention and technological enthusiasm, 1870-1970. University of Chicago Press.

Kerr, W. R. (2007). The Ethnic Composition of US Inventors: Evidence Building from Ethnic Names in US Patents. HBS Working Paper 08-006.

Kerr, W. R. (2013). US high-skilled immigration, innovation, and entrepreneurship: Empirical approaches and evidence (No. w19377). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kerr, W.R., Lincoln, W. F. (2010). The supply side of innovation: H-1B visa reforms and US ethnic invention. Journal of Labor Economics, 28(3), 473-508.

Khan, B. Z. (2005). The Democratization of Invention: patents and copyrights in American economic development, 1790-1920. Cambridge University Press.

World Bank. 2018. “Moving for Prosperity: Global Migration and Labor Markets” (Overview). Policy Research Report. World Bank, Washington DC.