Rachel Franklin is Professor of Geographical Analysis in the Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies (CURDS) and the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology at Newcastle University, and is a plenary speaker for the 2019 RSA Annual Conference. Her primary research focus is in spatial demography and the interplay between spatial analytics and demographic change, in particular quantifying patterns, sources and impacts of spatial inequality. For example, the projects discussed below investigate the role of spatial scale and context in understanding the manifestation and impacts of depopulation across neighborhoods, cities, and regions in the United States.

In 2017, the United States’ birthrate reached a record low, with total fertility rates below replacement level and at their lowest since 1978. Paired as they were with a recent historical reversal in increases in life expectancy and a highly politicised debate about immigration, these statistics helped contribute to a maelstrom of demographic unease. Into a context of long-term shifts in racial and ethnic demographic composition was now added the very remote but possible potential of eventual population decline. A shrinking population carries with it real challenges, such as lack of labor and increased dependency ratios, but also perceived challenges centered around decreased economic and political power: demography has long been political.

Of course, confrontation with population decline is on the horizon or a reality for several countries around the world, from Japan to Germany. For many other countries, such as the United States, current national-level population growth or stability only serves to mask immense shifts in population distribution that result in the hollowing out of cities and regions. It is here, at the sub-national level, that regional research finds an almost textbook application area: understanding the sources and impacts of regional decline is multi-disciplinary and inherently spatial, drawing attention to the importance of economic and demographic networks, interactions, and interdependencies.

A range of recent research has emphasized the importance of “places that don’t matter”—areas that may or may not be suffering population loss, but which have certainly suffered economically (Rodríguez-Pose, 2018). Another approach is to focus more specifically on the impacts of population loss for cities and regions and the need for a regional research agenda. A recent special issue of the International Regional Science Review, for example, co-edited with Eveline van Leeuwen, highlighted the myriad ways in which loss affects cities and regions but also how loss and aging affect urban policy finance (Carbonaro et al., 2018) and even residential segregation (Bellman et al., 2018). Another recent contribution, part of a larger volume addressing issues related to resilience and population loss, looks at the connections between a key engine of development, human capital, and population loss within U.S. cities (Franklin, 2017). Basically, when places depopulate, the demographic effects are about so much more than aging and these effects matter for quality of life, social cohesion, and future socio-economic development.

Of all the ways in which depopulation affects regions, many of the clearest challenges are oriented around transport. A recent book, co-edited with Eveline van Leeuwen and Antonio Paez, demonstrates that accessibility is a massive concern, as it brings together issues of funding, policy, vulnerability, and equity. For example, as regions and cities empty, the spatial mismatch between people and jobs may increase, particularly for vulnerable groups. In more remote areas, public transport becomes a less viable mode because of density and cost, while car ownership presumes a particular level of wealth and a younger age structure. There is hope of course: once problems are identified, effective policy may alleviate the burden of inaccessibility. Additionally, technological change, such as ICTs or “smart mobility” platforms may offer at least partial solutions.

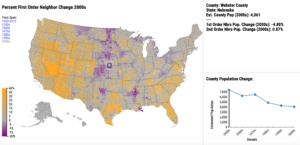

Turning back to the U.S., one thing that is striking is the sheer spatial and temporal magnitude of loss that has occurred in many areas, all within a larger context of robust population growth—and underlying it all is of course economic and political change, but also demographic change. Places lose population through a limited set of demographic mechanisms, all acting in concert: a surfeit of deaths over births, but also typically out-migration and a lack of net international migration. This interactive map of county-level population change (Figure 1 shows a standalone image) for the U.S. highlights the spatial demography of decline and lends itself to complementary sets of questions regarding the demographic impacts of loss: changes in racial/ethnic diversity, segregation, age structure, and income inequality, but also the importance of migrant selectivity and origin-destination migration connections.

Figure 1. County-level population change for the U.S.

What we talk less about when we talk about depopulation

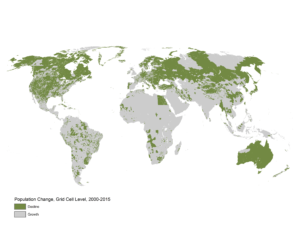

To a large extent the above observations are intuitive to regional researchers. There are other aspects of local and regional population loss we discuss less. For one thing, population loss is occurring everywhere (Figure 2) and this has likely always been the case. This adds an interesting dimension to research on urbanization at a global scale, for example. From the above discussion, we know that depopulating places may suffer in a variety of ways, but perhaps it’s time for more explicit consideration of the interdependencies between growing and shrinking locations.

Figure 2. Grid-cell population change for the world, 2000-2015 (data source: CIESIN Gridded Population of the World)

And what about potential intersections between depopulation and environmental change? Certainly, the links between over-population, food production, and environmental detriment have been the objects of research for decades and even centuries. However, while on the one hand a stable or shrinking population might be good for our planet, the local environmental impacts of population loss are much less well understood and possibly equivocal.

Some things we should be talking about

As regional researchers, possibly the highest value contribution we could make in this arena would be to help ourselves and others come to terms with the “okayness” of population loss. For a host of reasons, it’s time to think about a post-growth world, and that means economically and demographically.

That said, when we engage with the downsides of depopulation, we may also need a more expansive view. If decline is due to increased mortality or suppressed fertility and household formation (that is, women and young people not having children or forming households when they’d really like to), then local, regional, and even national population loss or stasis becomes a symptom of substantial societal malaise that shouldn’t be ignored, even if the outcome is positive. Moreover, taken in conjunction with heightened discourse around immigration and population composition (in particular, native-born population), perhaps dystopian narratives of increased social control around women’s rights and fertility aren’t so far-fetched. After all, it wasn’t so long ago that national governments in many countries limited access to birth control or abortion in an effort to increase fertility rates and, arguably, we see such restrictions emerging, de facto, in the United States today.

Or, if we’re talking about technological change and transport in shrinking areas, why not expand our scope to explore intersections between the automation of work, demographic structures, and depopulation? How can regions leverage these changes to their benefit?

Finally, although our fixation on regional and urban depopulation and aging is merited, it’s also limited: there will be a post-bulge era, it’s not so far off, and it will bring its own economic, social, and geographical challenges. We should be thinking ahead to that time.

I’ve only scratched the surface of what we do and do not talk about when we talk about population loss.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development, and want to elaborate your ideas in a different medium? The Regional Studies Association is now accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at RSABlog@regionalstudies.org.

References:

Bellman, Benjamin, Seth E. Spielman, and Rachel S. Franklin. “Local Population Change and Variations in Racial Integration in the United States, 2000–2010.” International Regional Science Review 41.2 (2018): 233-255.

Carbonaro, Gianni, et al. “Demographic decline, population aging, and modern financial approaches to urban policy.” International Regional Science Review 41.2 (2018): 210-232.

Franklin, Rachel S. “Shrinking smart: US population decline and footloose human capital.” Demographic transition, labour markets and regional resilience, Cristina Martinez, Tamara Weyman, and Jouke van Dijk, editors. Springer (2017): 217-233.

Franklin, Rachel S., and Eveline S. van Leeuwen. “For whom the bells toll: Alonso and a regional science of decline.” International regional science review 41.2 (2018): 134-151.

Franklin, Rachel S., Eveline S. van Leeuwen, and Antonio Paez, editors. Population Loss: The Role of Transportation and Other Issues. Elsevier. (2018).

Rodríguez-Pose, Andrés. “The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it).” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11.1 (2018): 189-209.